For quite some time now, the Lopez Museum and Library has been able to engage with the contemporary art world through the theme of dialogue. The very first example of this was a massive 2011 exhibition which established the parameters for this dialogue: contemporary art must engage with what the Museum already has. The strength of its collection lies not only in its art but also in its archive, where books, magazines, and newspapers provide sources for a history that deserves a fresh re-reading every generation.

Such a fresh re-reading may be what inspired this latest attempt at dialogue, Complicated, which is explicitly aimed at depicting in art how the Philippines has dealt with its colonial past. The engagement is primarily with two works that depict a romantic vision of the Philippines and two of its longest-staying colonial powers: “Espana y Filipinas” by Juan Luna (1) and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo’s “Per Pacem and Libertatem.” (2) Both of them are examples of the academic style which distinguished late Spanish-era work by Filipino artists. (There are other works from the Lopez Museum collection from different eras involved as well.) The dialogue is with the work of Leslie de Chavez, Mike Adrao, and Ea Torrado, who depict the challenges of post-colonialism through different angles.

Complicated’s confrontation with post-colonialism is thematically handled in spatial terms. On one side, the dialogue takes on an economic turn, with the American era and the introduction of modern Western capitalism (as we know it today) as a dominant theme. Studies of the Hidalgo work are alongside one of my favorite works from the show, De Chavez’s recent sculpture “Statue of Your Liberty,” which baldly depicts how America’s view of itself as a refuge for the free is underpinned, and gives rise to, the spirit of “free enterprise.” (3) While I suspect that his work critiques capitalism and globalization as the seedy underbelly of the message of freedom, there is an irony students of American history may note—one consistent theme in the American narrative is how immigrants can achieve success in entrepreneurial effort, but only up to a point.

On the other side, the exhibition explores other themes. The religious aspect is explored in de Chavez’s own depiction of the Lapiang Malaya (4), a quasi-religious movement that was suppressed following a bloody incident in 1967, and Hidalgo’s depiction of the assassination of Governor-General Bustamante, which now strikes me as being more politically potent. How religion is used as a political force is what I sense I see in common here, but my unease with how the modern nation-state aims to put itself in place of God is something I read into the logical extreme of movements like the Lapiang Malaya, which integrate folk Christianity into a nationalism-as-religion framework. On the other hand, I am aware that purely secular motives may have guided the murder of Bustamante more than anything else—religion was only an excuse.

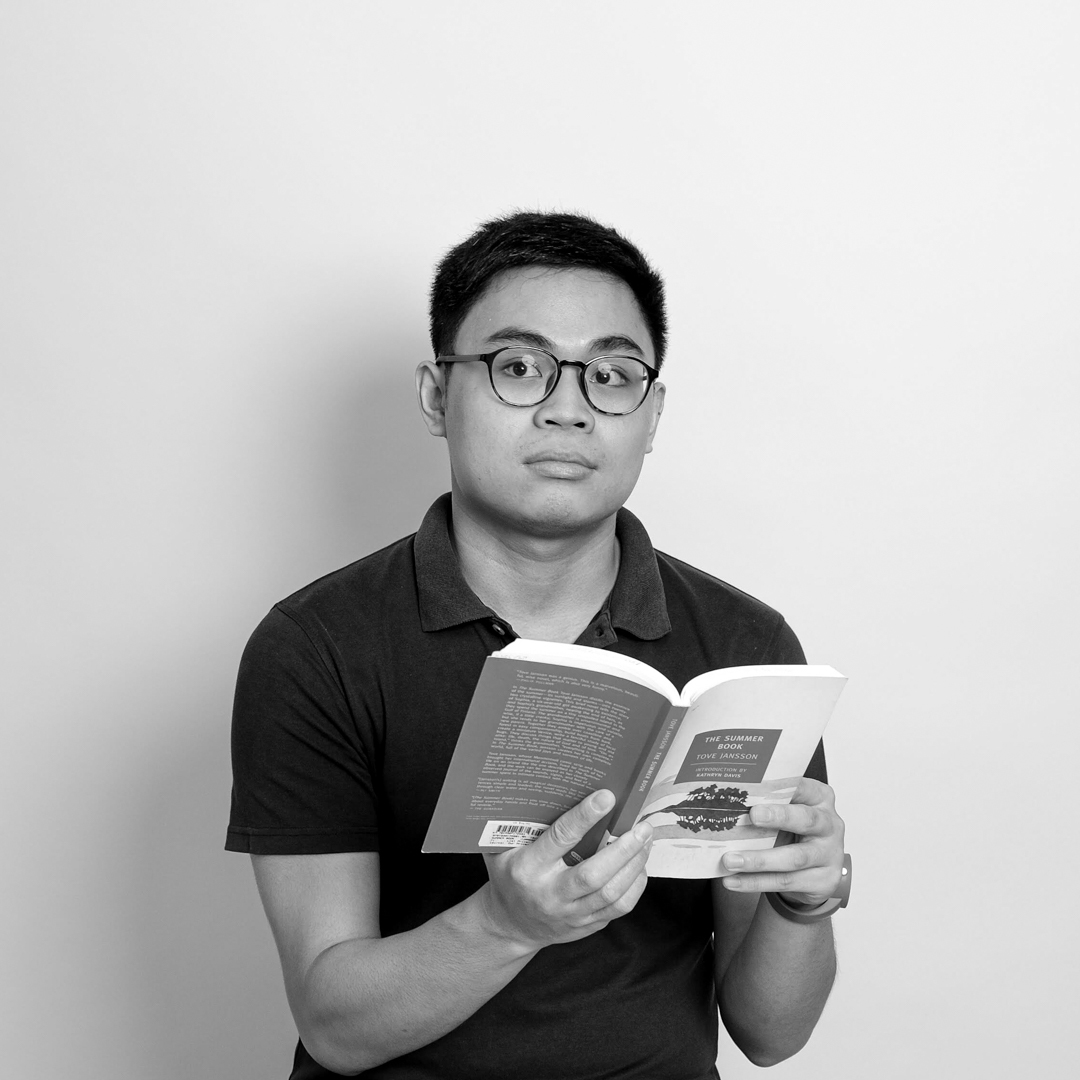

An excursus on the role of language, both visual and textual, in the post-colonial world, and on how Rizal most notably engaged the Philippine condition using the Spanish tongue which he learned, is what characterizes the next set of exhibits. The Rizaliana collection has played varying roles in the last few exhibitions organized by the Lopez Museum, and Vicente Manansala’s illustrations for Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere are what struck my attention. What I do wonder about is how exactly maps in this room fit into the over-all framework here, and I can only guess that these do represent the language of maps as boundary-setters. More striking, though, is de Chavez’s work in this section, “When the Medium Killed the Message.” (5) It rewrites a poem which we now know was not necessarily authored by Rizal in a patois that can only be understood in certain Internet circles. (It is probably a form of leet.) The use of this poem to promote resistance to “linguistic imperialism,” is made unfamiliar by a language which even less of us know.

The next space deals with women in art. This is where the Luna work can be found in dialogue with several contemporary works, most notably of Brenda Fajardo, Bencab, and Lee Aguinaldo. There is a connecting thread with the previous space in how Manansala’s Noli sketches of women characters are displayed, and even more with Ea Torrado’s contribution to the exhibit, “Sisa.” Her video performance depicts how womanhood has become marred by one of colonialism’s lasting effects: the modern nation-state can take on the corrupt violence of its former colonizers. As a work, it can (and should) stand alone, but to make the connection with the rest of the show, thematically, one needs to look beyond the obvious Rizal strand.

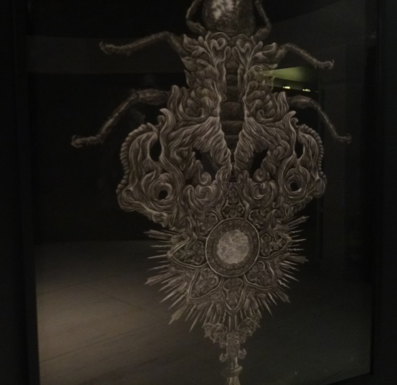

Mike Agrao’s work (6) represents a stylized reading of the paradoxes of post-colonialism, but I honestly felt that, for one, the dialogue was in part that of craft (with the Sanso work in a neighboring space), and for me, it struck the weakest notes. I felt that the way that the attempt to establish intricacy and obliqueness in craft to promote a message was not as clear on a first, or second visit, as I would have wanted.

I found this exhibition’s ultimate complication to be precisely the craft of contemporary art. If one wishes to re-read history afresh, as this show does, it might be an equally fruitful exercise to be aware of how the tools for such a re-reading came to become part of Filipino artistic expression. Here, I am glad that the temporal gap between the Old Masters and Torrado, Agrao, and de Chavez was filled with other work from a more recent past. And perhaps it is an awareness of the history of art that might resolve, or leave unsolved, the challenges of our complicated history, one that has placed us at the crossroads of empires and histories.