This is a coping corner. Coping, in architecture, refers to the process of covering or capping the termination materials of roofs, ledges, and baseboards, among others, to prevent dirt and water from seeping in the structure. Borrowing this technical term and relating it to the current state of cultural workers, artists, and creatives in the visual arts, in a time of a pandemic, at first, seems complicated. But not until one realizes that building an edifice is not totally different from the process of space-making (for exhibition-makers) and creative production (for artists).

Being involved in exhibition-making, there is a realization that as we build walls and rooms for the show, we also construct our own “truths” for us, and for the audience. When there are no concrete walls to cope, we are left with intangible walls to mold and bridge in order to augment a more timely, not alienating discourse, that spurs us to think within the realms of society and its social ills and conditions. Hence, the current situation we are in serves as an impetus to examine if one’s complicity and willingness to compromise have amplified the struggles of artists and cultural workers. Our response to the pandemic, whether we further allow the seepage of dirt or prevent it from damaging the entire system, determines the value of art to society and its place in history in the long run.

The coronavirus pandemic presents itself as an opportunity to rethink and assess the role of art. A Singaporean newspaper published a poll revealing that art workers fall under the topmost non-essential category during a pandemic. Meanwhile, the general Filipino audience views art, in its local context, as mere entertainment and a form of distraction to encourage everyone to stay within the confines of their homes. As galleries and museums shift online in terms of their marketing and programming, it has somehow diminished the elitist tendency of art and has democratized access of the viewing public to exhibitions, programs, and art. A discussion on the essentiality of art would only succumb to an endless debate. However, the nature of art remains open in order to fulfill a vital function, which is not limited and dictated by its currency in the art market.

The Philippines has one of the longest-lasting lockdowns in the world, compelling artists to be resourceful in using materials readily available in their homes. Paper Panic, an online exhibition comprising of artworks made from toilet paper, does not only address the issue on scarcity of art supplies. The works collectively respond to the humorous reaction of people hoarding tons of toilet paper in the middle of the virus outbreak across the globe.

As there have been a lot of initiatives to raise funds for medical health workers, a group of artists, on the other hand, reaches out to the jeepney drivers from the University of the Philippines in Diliman through the fund drive “Para! Para-an! Pa-abot Naman.” With the planned jeepney phase-out under the guise of public transport suspension, the livelihood of the marginalized and often-neglected sectors is at stake.

This pandemic, a health crisis that exposes the kind of authoritarian regime and governance in the country, is indicative that we cannot go back to normal, that creating and exhibiting artworks as commodity and for commercial consumption, is only part of a larger and complex art system. One of the many ways artists respond to the situation is through art-making that explores political themes, especially in a time of censorship and suppression of free speech. Art becomes a tool for documenting and archiving truths and realities that certain individuals are attempting to discredit and revise.

When freedom of the press is curtailed, there is no room for subtlety, but instead it calls for outright protest and opposition. Independent cultural organization Green Papaya Art Projects, on its culminating year, takes a stand against oppression and reflects on prevalent social issues through a series of posters expressing their dissent. Progressive group Panday Sining organizes workshops and webinars that orient and engage the public regarding the struggles and hardships of laborers, ethnic minorities, and the indigenous communities amid unrest and turmoil in the country.

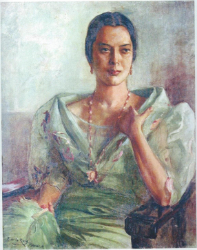

The pandemic has paralyzed not only the art world but also the system that operates it. A few days after seeing Ofelia Gelvezon-Tequi’s “Allegories and Realities” (probably the most important exhibition by a Filipina artist for this year), Manila has been placed in a lockdown. It is very unfortunate that the exhibit will not get the attention and appreciation it deserved. How often do we see works of a Filipina artist in a retrospective, particularly in an industry that is mostly dominated by men? The irony of it is that such pondering comes from another male perspective.

One should start questioning the institutions that operate the system — and by this, I mean the entire art ecosystem, including us, cultural workers, scholars, artists. We are our own individual institution. Putting finishing touches on a system that has long been damaged would not even suffice to bringing it back to its normal condition, if the rebuilding process would not start from its foundations.

Art writing is as significant as art-making—both are creative acts that serve a different purpose. The latter reflects the artist’s perceived truths, while the former is a way to interpret and articulate our shared realities. These acts then become our own “coping corners”: a mechanism to prevent seepage of the unnecessary and a safe space to grapple with the intricacies of art.

ABOUT THE PRIZES

In solidarity with the Filipino community affected by COVID-19, the Ateneo Art Gallery in cooperation with the Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc. has organized the AAG x KLFI Essay Writing Prizes to support writers affected by the crisis. With the theme “Thoughts and Actions of Our Time: Surmounting the Pandemic,” writers were encouraged to submit essays that reflect on or discuss the turmoil, struggles, initiatives, and expressions of hope during these trying times.

Through this Prize, the Ateneo Art Gallery hopes to extend assistance to artists and writers in its capacity as a university museum highlighting the Filipino creativity, strength, and resilience during this difficult period.

After receiving more than 100 submissions for the competition, six (6) winning entries were selected by a panel of jurors for each of the student and non-student categories. Writers of the winning entries received a monetary prize and their essays will be published by the Ateneo Art Gallery in an exhibition catalog accompanied by images of shortlisted works from the Marciano Galang Acquisition Prize (MGAP). Essays are also published in the Vital Points website, the online platform for art criticism developed by AAG and KLFI.

View the online exhibition for MGAP and the AAG-KLFI writing competition here.