The South-Korean born Swiss-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han pointed out this contemporary phenomenon called Undinge, the German word for ‘non-objects.’ He used it to refer to the gradual de-objectification of physical things and their translation to information, stored into the digital realm of clouds and bytes. To Han, objects are valuable as they act as ‘points of stability in life’. Much like a family heirloom or a routinary cup of coffee in the morning, they ground us. He wrote of it with utmost skepticism, perceiving it as the erosion of community and connection.

It comes to no surprise then that as I considered the works showcased at Vargas Museum’s recent exhibit, Fever Dream, Han’s philosophy dawned like a bittersweet trumpet reverberating through the halls of contemporary art, for in the exhibit was an abundance of pieces generally classified as ‘new media art’. This category encompasses the creation of a piece with the mediation of technology, usually with a computer or a camera, but also with different softwares. In an eon of never-ending information influx, how can they arrive as instruments to ground ourselves rather than as added noise to the digital delirium?

Fever Dream was a collaborative project between art institutions from PANAMA, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan. It illuminated the absurd normalcies we are pressed to swallow and tolerate daily—previously, the pandemic, and more recently, the continuing genocide in Gaza, the asphyxiating inflation, the intensifying warming of the planet, and other troubling affairs that we would rather, if we were being honest, dissociate from with the deluge of memes and reels like efficient saccharin pills. Each of the artists reflected specific anxiety-triggering issues.

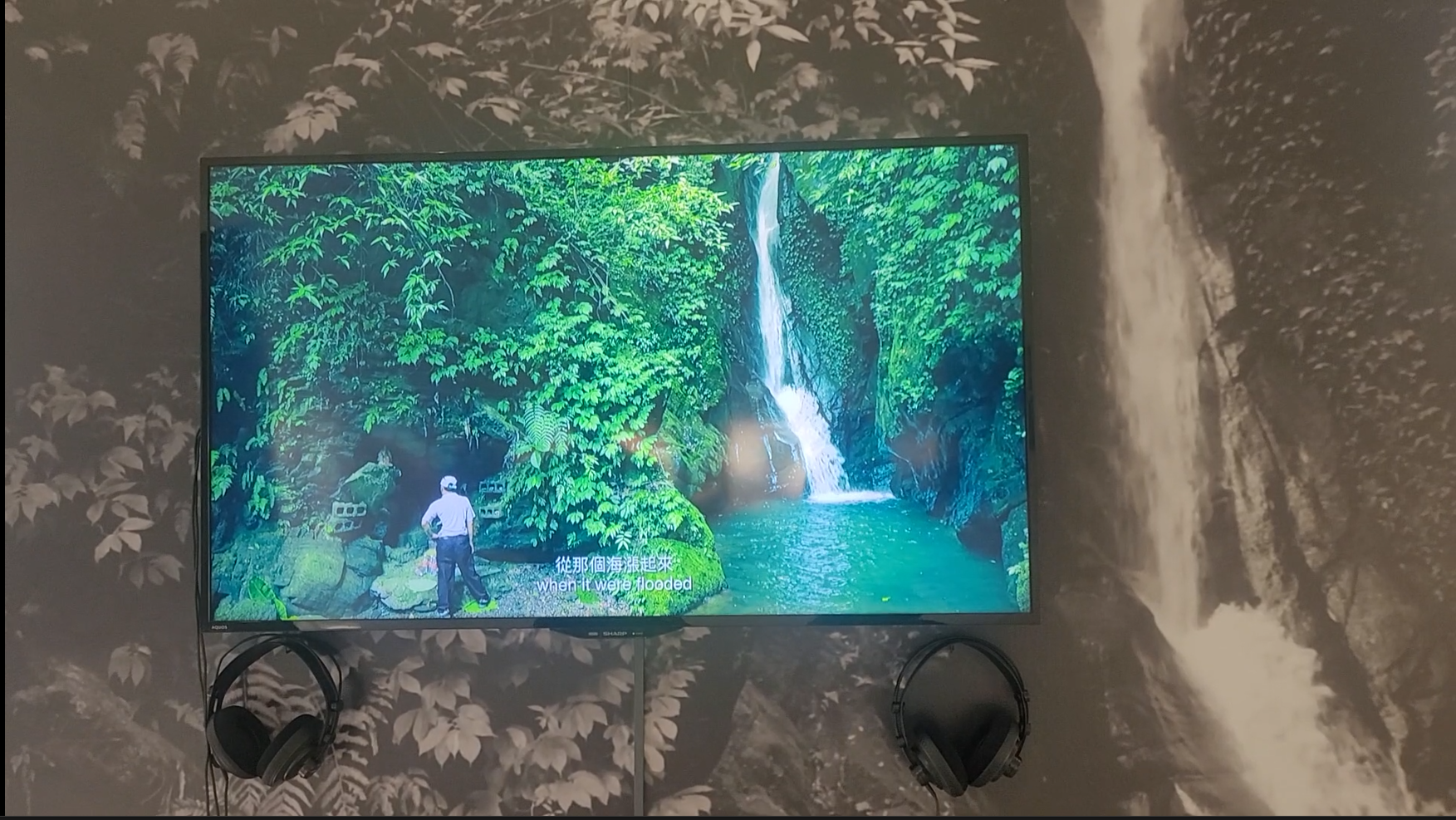

Veejay Villafranca captured in his array of aluminum sublimated prints the hellish conditions commuters face every day. He took photographs of the urban landscape, overlaying them onto each other to create grainy monochromatic vignettes. “Noise Herding”, a sound art made by Corrine de San Jose, used distortions of news broadcasts to highlight a time rife with misinformation and a growing distrust of authoritative sources. On the other hand, Posak Jodian’s (Taiwan) documentary “Lakec'' told of the story of the Fata’an people of Taipei, whose connection to a sacred river was severed by corporate projects, gnawing at their identity and instigating their displacement in a neoliberal society.

But this sea of computer-mediated art reflects the zeitgeist of our times and possesses a brilliance and magic distinct to them. The enchantment that came with watching Ana Elena Tejera’s 23-minute short film, “A Love Song in Spanish”, portraying, with measured earnestness and tenderness, the indelible effects of war to two lovers, is undeniable. Technology applied to art has made stories we may otherwise not understand intelligible through moving pictures and subtitles. Perhaps, a silver lining to Han’s philosophy of nonthings may be administered after all.

A significant aspect of this exhibit is its stated curatorial intention to decelerate our consumption, demonstrated in subtle ways by the nature of the pieces and in more palpable decisions like fragmented artist walkthroughs and an extended exhibition duration. The latter allowed for dialogues between the artist and the shifting public to occur. It must be noted that with the change of times, a new kind of audience is being born with their own set of ways, language, and culture. At best, these decisions bridge connections to this new audience that is slowly turning into a global civilization.

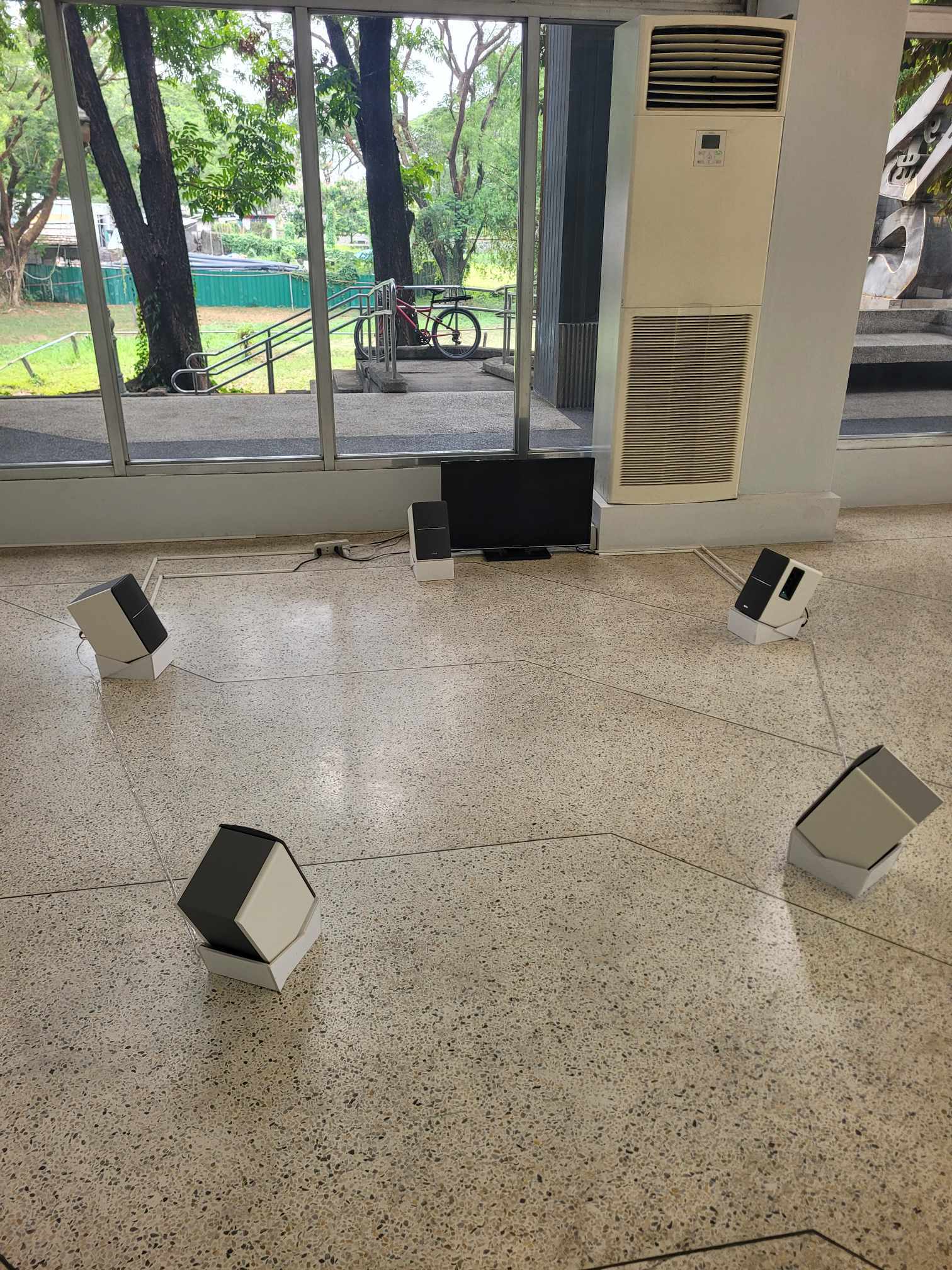

Additionally, a lyrical and synchronized unfussiness pulsate among the works, running counter to the sensation spasms of social media feeds and art fairs. It is volitional and visceral the way they were spaced, how each one existed in its fullness, and how luxurious it felt for the viewer to move around the vast uncrowded hall, keeping him from subconsciously treating art with addictive immediacy as one does with internet posts, a rhythm we have inherited from a society of infocracy.

The works that were featured in the show also held a temporal and contemplative nature to them, laying a mild hand of control on the viewer’s pace. For instance, the short films of Tejera, Jung, and Jodian followed individual timelines, inviting spectators to participate momentarily in a different diegesis, to witness their beginnings and ends.

Where more static works of art punctured telegenic pieces, archival documents from the museum’s collection juxtaposed the former’s intangible nature. A determining moment for me in Fever Dream was the placement of Jose Rizal’s literary piece, The Indolence of the Filipinos, beside idyllic paintings of shores and forests from the museum’s own collection. This point in the exhibit induced nostalgia for a bygone era when our bodies flowed with nature’s seasons, rather than the rushed ticking of the clock. Where there was a mother lode of pixel-formed pieces, stood these proud aged articles, things, and at once, an alchemy between new media art and traditional art arose, extending beyond mere coexistence to spurring dialogues and connections between different temporal points. Hence, the museum turned into a halcyon plot for long musings, not a site for brief encounters.

In this respect, Han’s Philosophy of non-objects brings to the fore the critical role of institutions to mediate transitions as the inevitable change of artistic practices materialize, and along with it, the surfacing of a new public with its own unique cultural codes and habits. Museums, in particular, can no longer simply act as repositories of physical artifacts– they must serve as intermediaries between traditional and digital art forms, ensuring that both ground us and effuse their own spirits, stories, and magic when invoked.

New media art and Net art have existed since the early twentieth century. Ever since, technology has been made exponentially graspable, convenient, and attractive. With the efficiency of cloud servers, transnational reach for “non-object art” has been made plausible as exemplified by Vargas Museum’s collaborating art institutions which also held their own iterations of Fever Dreams in their own locales. As we stand at the intersection of digital and material, the future no longer belongs to static spaces or solitary encounters. The challenge for institutions is to cultivate spaces where these intangible connections can thrive, fostering introspection and re-anchoring our human experiences in an ever-shifting world. In this sense, the Undinge can act as hyperlinks in magic-activating hotspots—spaces for ruminations in an ocean of fluctuations.