Born in 1942, Danilo Dalena has never been a stranger to the Philippine art scene. He began his artistic career in the 60s and 70s with his work as an editorial cartoonist for the Philippine Free Press and Asia Philippines Leader. More often than not, Dalena is highly recognized for his social realist works, from depicting harsh truths of the Marcos regime to various prosaic scenes set in the underbelly of Manila. In 1972, he was awarded the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ Thirteen Artists Award, further launching his career into becoming a prolific artist of his generation. Through the years, Dalena has mounted a multitude of solo and group shows, featuring both paintings typical of his style as well as experimental works. However, since having been battling with his decline in health in his old age, Dalena has not been as present as he was before in today’s art scene. Last Full Show, which was on display in the Cultural Center of the Philippines from December 10, 2016 to March 4, 2017, wished to highlight Dalena’s career and body of work, bringing to light recent paintings that had not yet been exhibited.

It’s rather apt for Dalena’s comeback retrospective to be held in the CCP. After all, his artistic career can be seen in tangent to this institution. From his Thirteen Artists Award in 1972, Dalena has often collaborated with artists in relation to the CCP and Last Full Show made palpable Dalena’s relationship with this institution. The CCP was not just a place where Dalena often exhibited, but was his own playhouse. Here, he was free to experiment with medium and with form, unbound by any notions of convention. Dalena has always made his work his own, and Last Full Show transformed the exhibition space and made it feel like one were stepping into a place once often inhabited by Dalena.

Dalena’s retrospective offers a playful and whimsical approach in displaying artwork in a gallery, which seemed to be both rooted in the conservative and the alternative. Many of Dalena’s more recent works were shown in a rather typical manner, foregrounding a white wall, apt in correspondence to a regular visitor’s eye level. However, many of his other works were displayed way above normal eye level, tilted diagonally, hung on an incline, or sat on the floor, leaning on a wall.

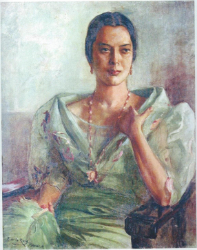

Interestingly, these unconventionalities on display give Last Full Show a rather homey feel to an often white and cold gallery space. Moreover, aside from having loaned from various collectors, Dalena’s retrospective also served as a showcase for his own personal collection of works that he had not sold or given to anyone. Last Full Show was not only an exhibition of works he had made throughout the years, but was also a glimpse into his personal life. Apart from portraits of his daughters, the exhibit also shows his reactions towards the concept of a National Artist, a replica of his bathroom host to a bust of Imelda Marcos, and some of his furniture including a jukebox and chairs.

On one corner of the gallery, a barber’s chair that Dalena often used in his home is carefully placed in front of a large painting of a church aisle. In other parts of the gallery, benches foreground his somber scenes of Alibangbang and Jai-Alai. Last Full Show invites the viewer to not only engage with the work, but to be a part of them, and incites different ways of looking in a gallery setting—a viewer seated on the barber’s chair is immediately confronted with a framed photo of Dalena on the same chair, foregrounding the same painting, on the wall across the viewer. The exhibition space holds paintings that once hung on the walls of Dalena’s living room, as well as its chairs and jukebox. And sitting on the benches, looking at paintings of theaters or Jai-Alai games, puts the viewer in a position similar to the subjects of the works, in a constant state of waiting for something—for a show to start or for a winner to be announced, but without actually finding out what lies behind that state of waiting.

It could seem obvious to look at an exhibit in relation to the viewer, in that its interpretations can lie seemingly right in front of you, but it is also in this sheer simplicity that stumps the viewer. Last Full Show provides a refreshing take on a retrospective, especially one featuring an artist so influential in Philippine art. Instead of sacralizing Dalena’s work in an austere space, this retrospective was able to make more accessible and relatable Dalena’s body of work. Perhaps Last Full Show is an appeal to look at exhibitions differently, to take away preconceived notions and a stance of overanalysis of a strict white cube intellectualism and move into a stance of immediacy and primary encounter—not to oversimplify a work, but to make a museum experience more candid. Not to hastily scour for subtext, but to focus on the present by being present.

Last Full Show may sound somber. Especially in his old age, one might think that this show would be the last that Dalena would ever mount. But Dalena would insist that it was not to be taken in such a grim way, but instead, as a celebratory performance with an all-star cast. Amidst all his melancholic scenes on loneliness and mortality, the exhibit contrasts these with the jovial and prosaic: from shoes greeting the viewer in the Main Gallery to peculiar condom sculptures. Dalena’s body of work has been large and expansive and Last Full Show not only invites the viewer to understand it as such, but to sit back, and enjoy the show both as spectators and participants of a highly anticipated performance of a master.