Worlds We Are is one of the most critical and coherent film programming I have seen in years. Curated by Prof. Patrick Campos and organized by MCAD, the three-day program featured moving-image works whose narratives revolve around Southeast Asia.

How do grandmothers tell their stories? And how does one make them tell these stories? Most apparent in the slated films in the program that use their grandmothers’ interviews/voices is the surrounding tenderness that stands in striking contrast to the harrowing contents of these narrations. It is from here that I was initially drawn in Worlds We Are where a number of works contain accounts from grandmothers and mothers relayed in various audio-visual forms. It is from this tenderness contrapuntal to the inconceivable that lays bare the many layers of Prof. Campos’ curation of twenty moving-image works in Worlds We Are.

With the program comprised of works “mainly by women situated in different parts of the globe, whose subjects are matrilineally linked and whose stories circle around places in Southeast Asia” (Campos), it becomes predictable, and to a point stereotypical, to correlate tenderness. But to simply associate softness with women is superficial. Instead, how do these women and their works recuperate softness and the very instability of memory vis-à-vis the grander scheme of history? How do tenderness and moving image become loci of possibilities and resistance?

Whether the subjects are blood relatives of the filmmakers or not, the affect elicited by these films rests on the personal. We uncover details accessible only through the relationship established by the artists with the subjects and through the trust ascribed by the subjects to the artists. We then become voyeurs to otherwise intimate minutiae of the past set against a backdrop of a very general history of Southeast Asia that we know—colonization, wars, displacements, regimes of dictators, coup d’etats, pandemic. The rigidity of history is broken down into tender recollections as we learn the plight of the filmmakers’ grandmothers and mothers (“Into the Violet Belly,” 2022; “A Worm, Whatever Will Be, Will Be,” 2022; “a spider, fever and other disappearing islands,” 2021; Memories of a Forgotten War, 2001); of women migrant workers (“Rasa dan Asa [Flavors, Feelings and Hope],” 2022); of friends under a dictatorship regime (“Yesterday [Kemarin],” 2008) and coup d’état (“February 1st,” 2015). As these experiences are mediated through audio-visual narratives we are suddenly privy to, we realize that this spectatorship will not be possible had these women not survived to tell these stories. The persistence of these personal accounts relayed through these moving-image works is commensurate with the persistence of spectral traces in the process of surviving where survival proceeds from the ineffable. The ability of these films to locate remnants of trauma in the present asserts their urgency and offers alternative ways of rethinking identities, histories, and communities. Worlds We Are further surfaces the “need for a new language to account for women’s experience” (Campos) especially in the face of “intergenerational trauma experienced matriarchally.”

Not only are the films personal because of familial/communal relations shaped by an inconceivable past, but because of the entanglement of the self in the present—the geographical and cultural displacement of the ancestors for instance now becomes innermost forms of displacement that need articulation, which cannot be accommodated by the confines of history and objectivity. Moving image then lends itself as a site of utterance. The inclusion of works that directly locate the self amidst forces that have shaped and have been continuously constructing it (“The Studio AKA The Songs That Sang Her,” 2015; “Haya,” 2022; “Sisyphus’ Cat [Con mèo cua Sisyphus],” 2022; “Casting a Spell to Alter Reality,” 2020; “Kassaram,” 2020; Fifth Cinema, 2018) draws us to a re-examination of historical and colonial encounters through intimacies—that the personal is not only personal but always trans/national and political.

While the past shapes and haunts the present and possible futures (the self becoming inextricable from imperial forces), the narratives in Worlds We Are refuse to be defined solely by histories of subjugation, rather they reveal how hauntings are ongoing contestations necessary to puncture on historical truths and create fluctuations to a society preoccupied with the present. By speaking from the position of I, the power to write one’s own narrative allows one to reclaim the self, accommodate and process the past in the present, and recuperate representations not as mere victims but as humans with agency. The intricacies of atrocities are also better understood and relayed by belonging in these communities and by being a woman in these communities. The collation of an array of moving-image works from 2000s to present that reference on different time periods in Southeast Asia is a vital curatorial consideration to illustrate varied struggles that further question our place-making. From American colonization to other forms of contemporary subjugations in Southeast Asia, we recognize the parallels and differences that make us rethink the concept of “neighborliness” since this “regionality is premised on spectral spaces” (Campos). These narratives also serve as counter-cartographies in the interrogation of our spatio-temporal contexts which ultimately translates to the interrogation of our histories and identities ("A Day Without Sun in Mengkerang [Chapter One]," 2013; Expedition Content, 2020; "To Pick a Flower," 2021; "Nightfall," 2016; "Night Watch," 2015; "The Cave [Puke ng Ina],” 2019; "February 1st," 2015; "Gikan Sa Ngitngit Nga Kinailadman [From the Dark Depths],” 2017; Memories of a Forgotten War, 2001). We determine that “the we that the I belongs to necessitates an encounter and recognition of the other as difference, with whom the I can better understand oneself, sympathize and stand in solidarity” (Campos). We identify ourselves in these narratives, but we also discern that these are not our stories as we both draw parallels and maintain multiplicities of identities and histories.

What also makes Worlds We Are pivotal is its reflexivity on the ethics and limits of representation. The absence of any direct representation of trauma and violence in the curated works invokes the lyrical. However, this lyricism does not stem from a romanticized standpoint, but from attempts to turn to other devices and audiovisual cues that endeavor to navigate the unspeakable. By moving away from the spectacle of explicit depictions, the hauntings are rendered obliquely but are reinforced more substantially and viscerally. From the slippages that are seemingly mundane, we fathom how trauma bleeds into the present, how anxieties linger and await in the future, how it is in the aftermath that atrocities can be realized as both conceivable and inconceivable—that the ghosts of the empire lurk in the silence of the streets, around the house and the dinner table, in the ear or under the skin.

References

Campos, Patrick. "Worlds We Are." MCAD X Moving Image: Worlds We Are, DLS-CSB, 2023, https://www.mcadmanila.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Moving-Image_Worlds-We-Are_Booklet.pdf. Program booklet.

---. "Curator’s Talk: Patrick F. Campos + Q&A." Presentation, MCAD, 14 Sept. 2023.

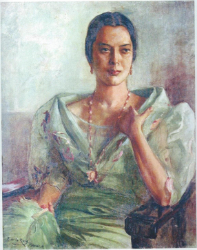

Lai, Mickey. "A Worm, Whatever Will Be, Will Be." 2022. Still image.

Seno, Shireen. "To Pick a Flower." 2021. Still image.