There’s something terribly aloof about Karl Castro’s Social Fabric.

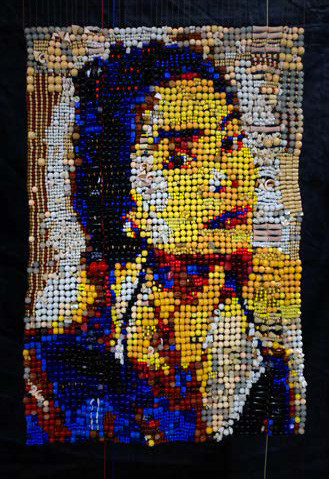

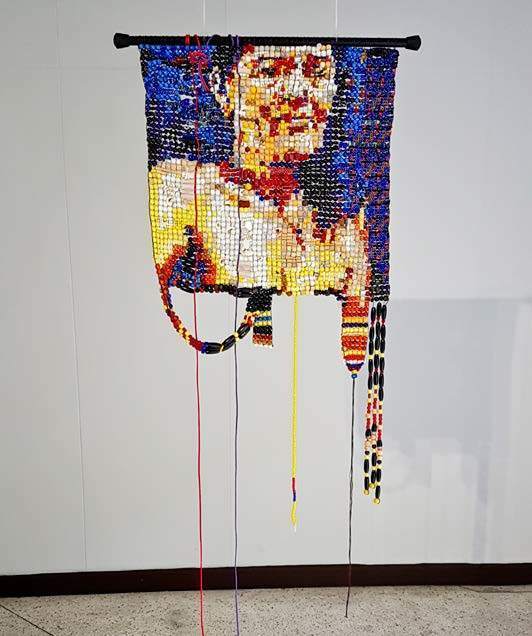

First the gesture: it purports to busy itself with the quotidian, the “everyday,” here meant to be seen from afar—but then, what kind of everyday? Look, his images seem to say, isn’t it already apparent? Awoman taking off her top to expose her breasts, a figure masturbatingin bed, a young man looking directly to the camera while a group of men have an orgy behind him, their silhouettes coalescing. There is a sense of boredom here, only that boredom is mediated by layers and layers of meaning: he wants you to come closer, see what it’s made of. But the images aren’t made of pixels, they’re made of beads, wood,glass, plastic, metal, and the entire image cannot possibly fit in yourpalm. Isn’t it still apparent? When you open your laptop, or when you take out your cellphone from your pocket, can’t you see, there is an eye watching, a tiny peephole that can replicate your face, your body into a million manifold.

Henri Lefebvre, architect of pleasure, describes the everyday as repetition with variation, like when a dancer repeats the same gesture over and over until we realize that none of her gestures are really alike. It is only now through smooth technologies where the hyperreal not only becomes an extension of what is considered “concrete and palpable”reality that one can catch a glimpse of the infinitesimal and the finite, it has also become an available continuum of a “complete self.” There is a sense of completion, a finality, for example in an Instagram post showcasing either what one is having for brunch or a partial nude; the image cannot escape its materiality, it cannot escape its definite meaning, simply a picture of food and body part, it cannot escape the grid and the pixels. Castro somehow for a moment foregoes this act of completion, mistaken for a snapshot or the now ubiquitous screenshot: in the portrait A woman pulls down her tube top, the bottom of the work looks like it’s in tatters, simulating a ripped hem or maybe a possible surge, the image escaping its own imagery, and so it is with the other two female portraits, An old lady puts on her lipstick and strapless bra,and A young woman pimps her locks; what then adds to this appearance of mere analogue assemblage is that due to the inconsistency of each bead’s roundness and size, the images, unlike their smooth, pixelated provenience, become crude and distended, giving it texture, but also robbing it of virtual depth.

A digital warning: once something is uploaded on the Internet it is there forever. There are two contending technologies of everyday in Castro’s Social Fabric but there seems to be no interrogation happening between the two, just two separate monologues deaf to what they’re trying to problematize, the erasure of the repetitive but variating everyday: the traditional technology of weaving and beading, which Castro tries to approximate by actually using the loom, a traditional means, is de- emphasized by several assumptions that relate to body and labor. Here he assumes that the weaver is a singular body that is intent on producing an image or textile, what is now only understood in touristic terms as “art object,” when in fact the taga-habi not just simply dilutes or “summarizes” the community’s dreams and aspirations via the object produced but actually re-enacts these dreams and aspirations in the very gesture ofweaving. Labor here is also defined in a traditional sense and so having traditional value; what is re-appropriated here as product with value is thebeaded image finally presented, but without pointing to the precarity ofcurrent labor practices in hyperspace, that is, real value is removed and placed elsewhere, so a bunch of body getting paid to have an orgy in front of a camera, as in the deadpan piece A young man chats while his fellows congregate is not really valuable because it is not considered labor in the traditional sense in the first place.

Images trapped in beads. Though maybe there is something suggestively violent here: the closer we get to Castro’s images, the less we see whatthey really are, what they really want to mean, like selfies, “dick pics,” #sendnudes thrown into the virtual without any consequence, all floatingand aloof. Beads if not sewn tightly, fall apart, scatter, make noise once they hit the ground: an everyday object, familiar.