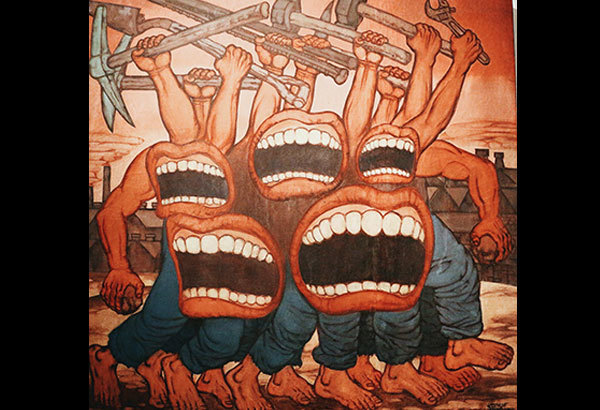

The five angry mouths painted by Neil Doloricon stand in soundless protest against aggressors invisible beyond the frame. Their hammers, wrenches, shovels, and rocks —held by an illogical set of eleven arms — are set to raze some structure or another. There aren’t exactly picket signs telling wide-eyed onlookers the reason for their riot, although the image tells the story clearly: starving, angry mouths spitting native curses like bullets fired from an old revolver.

Doloricon’s “Galit ng Masa” (1990) was one among the few paintings in Lopez Museum’s “Drawing the Lines,” an exhibit curated by Ricky Francisco, shown earlier this year. Works by artists Jose Tence Ruiz, Francisco Coching, Danilo Dalena, Liborio Gatbonton, E.Z. Izon, and Doloricon reintroduce the agon and fury surrounding comedic political cartoons.

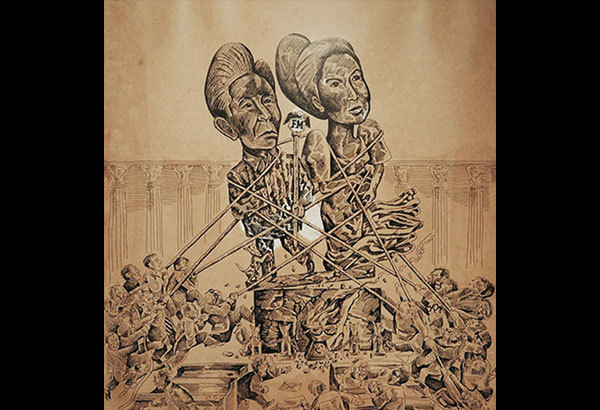

In the ’60s, national aesthetics veered towards modern and conceptual art. The Cultural Center of the Philippines, in particular, ordained by Imelda Marcos as the country’s messianic Parthenon, was to actualize the symbolic coming of the modern world — and to better orchestrate, of course, the Marcoses’ making of myths.

While the exhibit displays no installation of the imposing modern structure, “Drawing the Lines” explores how form evokes figments of the ideal, with the inclusion of paintings commissioned during colonial times. In a talk held by the museum, Doloricon gave a brief commentary comparing formalism and cartooning: “Pipinta ka — lahat ng [hirap] mo, bibilhin ng may pera, ilalagay sa kuwarto niya. Pero sa print, hindi ka nawawalan ng kopya; hindi ka nangungulila.”

Whether it be a commissioned image of a coming utopia or the all-encompassing narrative of national identity, cartoonist Jose Tence Ruiz similarly states: “The image is owned by (the one in) power.”

Doloricon and Ruiz, however, belonged to a raunchy tribe of artists who popularized social realism in the ’70s. As the media conjured its myths of idealized progress, the left-leaning Kaisahan collective launched its visual rhetoric of resistance.

Presenting vote-buying agendas (E.Z. Izon’s “Bribing the Voters,” 1959), workers wading in muck (Liborio Gatbonton’s “Laborers Must Have Justice,” 1970), and smug-faced politicos completing the circus of crocodiles and vultures (Doloricon’s “The Evolution,” 2000), newspaper illustrations provoke and irk, exorcising art of the different eras’ many fashionable delusions.

Painters, who lived the grind of producing five editorial cartoons a day, confronted and articulated the woes of the working class. Art was re-animated with grain and grit, and irreverent comedy was made divine.

With most copies rendered in tones of black and white, binaries raged within a single divided page. Evident in E.Z. Izon’s “Welcome” (1970), Liborio Gatbonton’s “Laborers Must Have Justice” (1970), and Doloricon’s untitled cartoon portraying GNP growth (1996), the disempowered and the political elite inhabit common ground, occupying their designated positions in the polarizing theater of the frame.

The lines are drawn, the roles are established, and the throngs of bodies, vices, and afflictions are all named and marked. Here, the exaggerated and the seemingly limiting two-dimensional portrayals do more than reflect a harrowing political milieu; symbolically, the black-and-white images rip, raze, and resist art’s complacent surfaces: the mythological, the lofty, the grand, the multi-colored artwork flourishing in the annals of private living rooms. “We popularize print, because art isn’t always bought,” says Doloricon.

While print isn’t bought, the very building where the Lopez Museum now stands tells another story: how political power holds sovereign sway over the source that makes the image. The Manila Chronicle, which once operated inside the building, closed its press during martial law. At the height of censorship when cronies wielded their influence over the press, the media figured as the government’s mouthpiece.

“Drawing the Lines” launched right before the riot of the elections. While there may not have been a greater panoptic force that has influenced its curation, the museum is associated with one of the country’s largest media conglomerates. It begs the question of whether images raging within the frame can ultimately be free of ownership, of power, and of politics’ million false propagandas — even in a place as democratic as a museum.

Works created after the Marcos era such as Francisco Coching’s “Ninoy Lives” (undated), Ruiz’s “Let Us Not Reject the Benefits of the Sun” (1987), and Doloricon’s untitled ship of politicians, suggest that the same strained rhapsodies resound, whoever the hero we elect. Unlike comic strips which render satisfying resolutions, in cartoons, there isn’t exactly a redeeming finale.

Political cartoonists wait for new regimes to cough up the next issues to wrestle with and the next caricatures to draw, ever keeping the dialectic pendulum in place and swinging. Doloricon’s eternally raging mouths raise their protest against authorities they can’t, quite literally, even see. Even in the dichotomous, two-dimensional theater of cartoons, not all antagonists are easily labeled or in attendance, leading our minds to stalk what the lines leave absent: the set of aggressors yet invisible beyond the frame.