The interfaces of Philippine art history are fascinating territories: fecund areas where past and present practices transit and intertwine, marked by both metaphorical monuments to the muse and moments of real world resistance.

The Philippine Contemporary attempts to capture this process of flux on an ambitious scale. On view since February 2013, this permanent exhibition occupying the entire second floor of the Metropolitan Museum of Manila presents a collection of over 200 works from the past 98 years, from 1915 to 2013. It also comes at an opportune time for expanding critical discourse on Philippine contemporary art, as the country prepares to participate the Venice Biennale after 50 years in 2015.

Ascending the flight of stairs, the museum goer’s first encounter is not with the image, but with words: a staked claim to embody both the Philippine and the present. One is immediately surrounded by texts and timelines: contextual anchors bearing the weight of unfolding histories and disclosing particular conditions of artistic production.

Preparing to navigate through nearly a hundred years of Philippine art is not an easy task. One always runs the peril of omissions: stories oversimplified, continuums ossified and watersheds overlooked. What, however, prevents The Philippine Contemporary from plunging down this dangerous slope can be described as something short of a curatorial coup: the exhibition design veers away from conjuring a grand, definitive narrative of Philippine art history’s greatest hits and, instead, attempts to soberly scale both “the past and the possible” through a chronological and reflective survey of works.

The exhibit has three main themes—Horizon,Trajectory and Latitude—which appropriate the language of cartography, hinting at how all this is also an attempt to map the field of Philippine contemporary art.

Yet the weight of history need not intimidate the uninitiated. For some, the truly surprising journey may well be this visit into the past. In the hall for early 20th century works in Horizon(1915-1964), National Artist Guillermo Tolentino’s Neoclassical sculpture Venus(1951) beckons one into a room mainly populated by changing images of the feminine, testifying to the representational shift from the conservative to the modern: from Fernando Amorsolo's dalagang bukid (1915) and Ricarte Puruganan’s college graduates (1935) to Cesar Legaspi’s Bar Girls (1947) and Victorio Edades’ MoroGirl (1950).

The narrative starts with these feminized markers of both nascent nation and emergent Modernism: times when the Philippines was displayed, like the proverbial nude, to the Western gaze from the 1904 St. Louis Exposition to the 1964 Venice Biennale. The progression of figurative works into the graphic arts and abstraction points to how artists responded to aftermath of foreign occupation: weaned away from centuries of feudal commitment to religious representation, embracing both the secular moment and the colonial imagination by the middle of the 20th century.

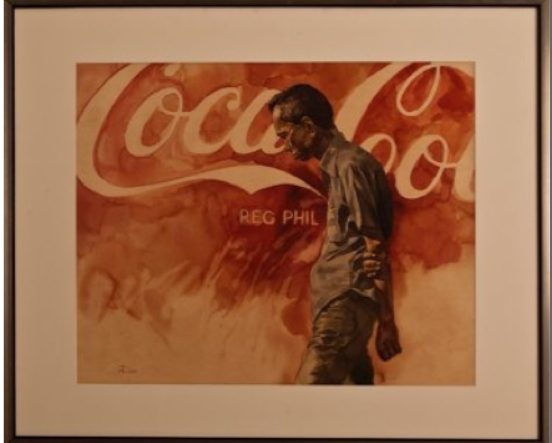

By now, the images one encounters seem to shift: spanning a wider range of styles and contexts in Trajectory (1965-1983). This section is a tribute to the waves of creative efflorescence during the most politically turbulent times in Philippine history. Seemingly polarised but equally pioneering strategies of artistic expression and representation result from both hybrid Modernism and local reality: from Neoexpressionism to conceptual art, from abstraction to Social Realism.

Crossing over to the opposite end of the hall, Latitude (1984-2013) populates half of the exhibit space with works produced during the past 30 years. This segment underscores how diverse artistic practices are in this age of wanton globalisation and multi-faceted crises: from the persistence of painting to the popularisation of performance, video and photography-based art; from the emigre to grassroots-basedartists; from auction house darlings to artist collectives burning effigies in the streets of Manila.

All in all, the exhibition features hundreds of works that can be examined and enjoyed on their own terms, in their own little worlds and horizons. But epiphanies and discoveries also reward viewers committed enough to tease out connections between individual objects and collective styles, across historical periods and changing relations of artistic production.

Interesting contrasts, for instance, can be drawn between works coexisting along parallel timelines. One can explore similar dates of origin: how, for instance, the year 1978 connects both Antipas Delotavo’s haunting portrait of the dispossessed proletariat in Itak sa Puso ni Mang Juan and Romulo Olazo’s diaphanous and ethereal abstract forms.

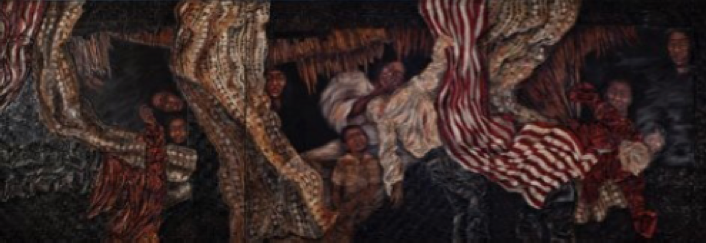

The exhibition makes visible shifts within subject matter and media back and across time. For instance, one can trace how intermedia and installation have articulated both nationalist and indigenous aspirations, intersecting during the early 1980s with Junyee’s seminal Wood Things and Imelda Cajipe Endaya’s Pasyong Bayan, later progressing into a critique of the postcolonial in Gaston Damag’s appropriation of the Ifugao bul-ul inYou and Me. Similarly, works such as Danilo Dalena’s 1982 portrayal of the Feast of the Black Nazarene resonate with Gerardo Tan’s more recent PhosphorescentGospel installation. Indeed, semiotic interfaces abound in this show, limited only by how one frames these connections.

Like all attempts at surveying, this show is not without its omissions and gaps. More can be done to eventually include works that can affirm the broad scope of artistic production in Visayas and Mindanao—raising the question of whether the contemporary is also contingent on place, and not only time. More space can also be given to practices operating on the fringes of mainstream art, representing he subaltern in the way Alfredo and Maria Isabel Aquilizan’s 2013 Mabini Art Project calls attention to the little stories that have fallen in between the cracks of art history.

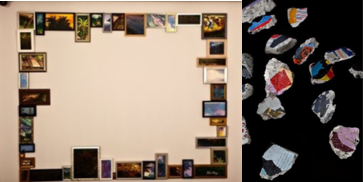

In the end, the exhibition can be weighed as a strategic but ever-shifting site for critical discourse. Like Poklong Anading’s Fallen Map series made from painted concrete rubble, the show collates a body of objects discrete yet intensely interconnected by their shared histories. By historicizing the aesthetic and the artifactual, one can better navigate the current and represent the present—hence continuing the story of the Philippine contemporary.