It is this sense of loss that haunts and electrifies Complicated,an exhibit currently on view at the Lopez Museum and Library in Ortigas Center, Pasig City. For the three emerging artists Mike Adrao, Leslie de Chavez and Torrado, what is lost, and therefore has to be sought if not recovered, is a sense of national self, an authenticating identity amid the complex imagery of our colonial past and recent modernity. They were asked to engage with the extensive Lopez Museum archive—paintings, photographs, maps, journals, even Jose Rizal’s personal memorabilia—to come up with artworks that reveal this nebulous and fugitive idea(l).

But if there is something that the exhibit, curated by Ricky Francisco and Ethel Villafranca, asserts, it’s that this national self or soul, or whatever you wish to call it, is neither easily recognizable nor transfixed, characterized as it were with violent shifts, upheavals, and instabilities, and has to be interrogated unrelentingly in fraught conditions of artistic production—from de Chavez’ subversion of Western symbolism (and its attendant ideology) to Torrado’s exquisite contortions to Adrao’s anthropomorphic perorations. Hence the title of the exhibit.

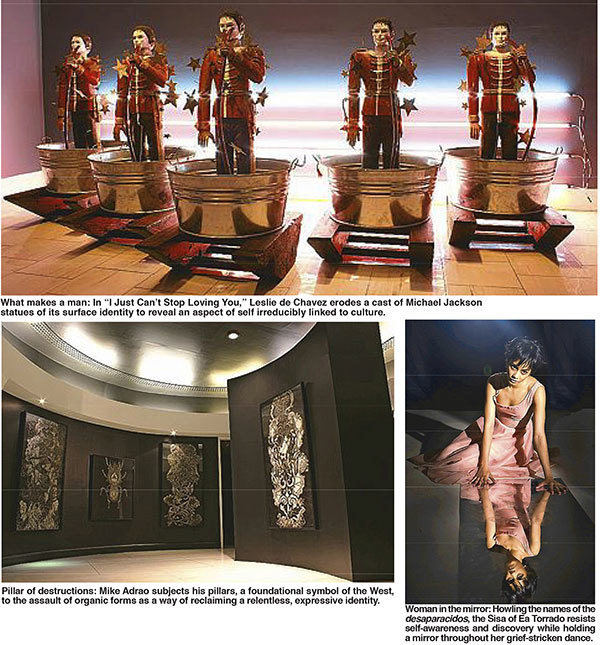

The works most representative of this difficulty are those by de Chavez who confronts head-on not only colonial imagery (and how the subjugated were forced to see themselves by and through it) but as well as unmistakable, and still-present, capitalist signs. In the installation I Just Can’t Stop Loving You, de Chavez positions handcarved wooden statues of Michael Jackson in basins, water from a hose trained on the face. In time, the white paint that covers his face will be eroded, his “true color” revealed. The use of Michael Jackson, who had a conflicted relationship with racial identity during his life, is a telling statement on some essentialized component of self-related to culture that cannot be erased.

While I Just Can’t Stop Loving You, along with State of Your Liberty (which shows a replica of the Statue of Liberty turned at angle upside down, revealing a shanty crammed with billboards of consumer products, freedom purchased by capitalism), seems to be a grim assessment of a conflicted notion of self, de Chavez, by pushing his work to the realm of camp, employs humor, a powerful tool of the oppressed: the ability to laugh at, and in the process undermine, authority.

This is evident in Not Everything that Glitters is Gold, a direct engagement with Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo’s Full Study of Per Pacem et Libertatem, which served as model for the larger work exhibited at St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. The fair showcased the Philippines’ various “exotica,” including members of indigenous tribes, to boast of USA’s latest acquisition and display, in a zoo-like atmosphere, the impossible-to-assimilate Other. (For context, photographs from the fair are also exhibited.) By choosing a quadrant to reproduce and then lavishly covering it with gold paint, de Chavez emphasizes, while at the same time disassociates, Hidalgo’s work from its commissioned, US-endorsed roots. The actual painting exhibited at the fair, by the way, is now lost to history.

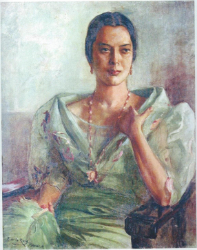

Claims to specific traits of what constitutes the Filipino identity are bound to be unsatisfactory but Juan Luna posits it as essentially feminine, if not female, in España y Filipinas, possibly the most famous painting in the Lopez Museum collection. Spain and the Philippines are personified by two women climbing stone steps, with the former leading the latter toward enlightenment, meaning out of ignorance. This image of a young, delicate maiden would eventually be interrogated and replaced by the women in the works of National Artists Benedicto Cabrera and Vicente Manansala—at once sensuous and sensual. Deflecting the female gaze back to herself is the Sisa of Torrado who is griefstricken, hysterical, wildly expressive.

Casting the menacing shadow of colonialism is the series of interconnected works of Adrao that shows anthropomorphized pillars whose Western motif slowly rots to reveal organic forms. The pillars are juxtaposed with renditions of termites (which create the “colony”), agents of consumption. Adjacent to Adrao’s works are the stark figurations of Ang Kiukok and Juvenal Sanso that echo not only their motif and coloration but also their somber mood and dark energy. No final emancipated figure is revealed, just the perpetual process of moulting and transformation.

Complicated stitches two, though not exactly coterminous, worlds at once: the imagery of our colonial past and the contemporary compulsion of art-making, the hybridization of both resulting to startling, ironic, meaning-laden figurations that are reflective of a deeply private, as well as an acutely social, consciousness. That the artists felt no qualms in referencing and even subverting artworks once perceived as sacred objects underscores the agency which, through its symbolic articulations, can have a glimpse of itself. No image is spared. In the case of Sisa, she only has to lift the mirror to see herself.