The word contemporary, in my mind, has been one of language’s savory garnishes. Nowadays, it is an ingredient many would look for, the same way one would look for seals of approval from certain goods. It has replaced the past approval—the ‘modern’ movement. It is almost as delectable as it sounds: con-tem-puh-rary; rolling down from our lips like a lure. It appeals like an appetizer, always served before the main course—contemporary fiction, contemporary design, contemporary management, contemporary gardens, and so on. One seeks it in order to validate oneself as part of the now, as someone who is in tune with the times, fashionable and dynamic. It only takes one qualifier for anything to be considered as timely.

Which is why my first encounter with the phrase Philippine Contemporary opened simultaneous tracks for both caution and anticipation, being mindful on how the idea of contemporary can be easily latched onto any other entity; and optimistic, because if it is what it has claimed to be, then we have something in our hands a feat that is yet unmatched in terms of indexing local art.

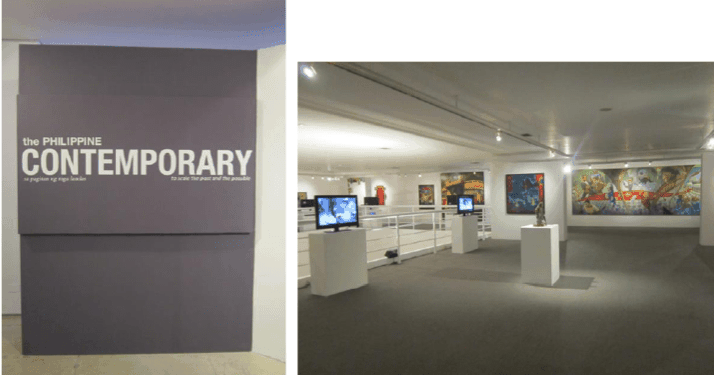

It seems apt to begin with the very manner on how such feat is titled. Contemporary here is not served as an introductory label but as the real subject of the event. Its modifier—Philippine—is relegated as foretaste to the real meat. This serves as an indication of what Dr. Patrick Flores, the curator, might have envisioned for the revamped Manila Metropolitan Museum—to be able to scale the past and the possible. There is a degree of open-endedness within that frame, an inexactitude. It is as if to say that it does not serve to define what represents contemporary art in this land, but what can possibly stand out and illuminate as an inherent Filipino stature about certain contemporary works.

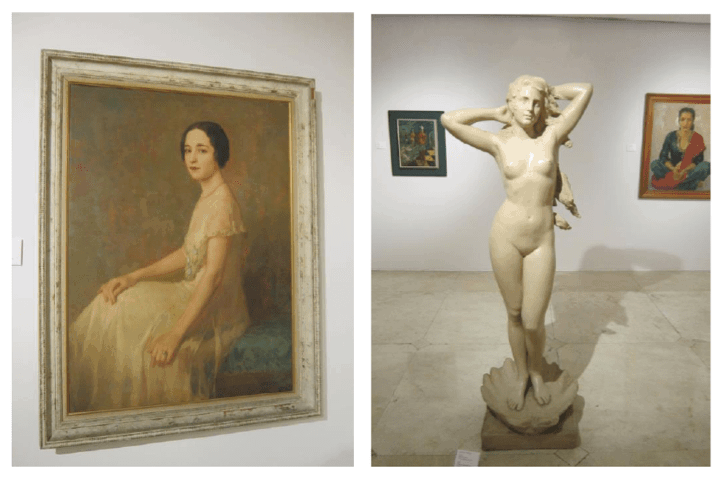

The massive volume of artworks is charted using five reference points: Horizon, Trajectory, Latitude, Sphere, and Direction. Here, the curator assumes the cartographer’s role of surveying an uncharted land that has undefined boundaries, and invites his viewers to take on a mapmaker’s stance as well. During the opening night (staged for artists, selected guests and patrons), live music and performances by experimental artists, along with an array of video projections running across the background, quickly set the tone for a truly avant-garde atmosphere. On the platform across the stairs leading to the main view of the exhibition, the fictitious characters of younger generation illustrators, Louie Cordero and Mark Salvatus, terrorizes the opposing walls, which infuse the punk attitude of graffiti. It is at our arrival at the exhibit’s main view on the second floor where we experience the first sharp turn from what momentarily felt like false anticipation—we are greeted by the sudden solemnity of the portraits by Fernando Amorsolo, Victorio Edades, Carlos Francisco, and other modernist canons.

As we continue to follow the natural course of the gallery, we sense a loose, chronological structure on how the terrain is plotted, beginning from the pioneering masters, with Amorsolo’s 1915 portrait of Fernanda de Jesus, loop-ended with works by younger artists like Catalina Africa, who was born in 1988. The exhibition, through a roundabout path, narrates a progression of styles and movements through at least 150 contemporary works.

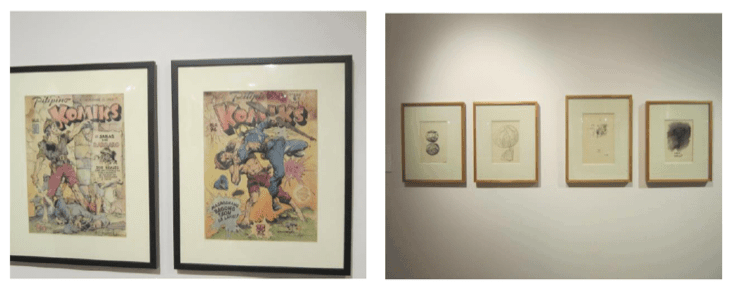

There are a lot of things that can be said about the method of indexing, especially how the works are put together. In trying to stay true with the topographical concept, one may ask, why the arrangement did not start at the center to later branch outward, as how a world or piece of land would usually develop? Why are we encouraged to rummage within a closed circuit, a loose timeline instead of freely traversing an exotic land with distinct quarters? Why are we bound to see a Francisco Coching comic book without a Nonoy Marcelo anywhere near? The same holds true for an Antipas Delotavo painting that is far removed from the works of Sanggawa and Salingpusa.

Though these questions may be valid, they are only one of many possible configurations in presenting such an immense collection. But in reality, any concept won’t do as much in alleviating the experience from any sharp turn, from the influx, that the visual art can inflict on the senses. Contemporary art is after all, the sum of withstanding disciplines.

The applied chronological order, to everyone’s advantage, is the most democratic, neutral. It stays true to the way of the museum—to provide the specimen and leave the analysis to the audience. As Dr. Flores openly admits in his statement—“it proposes a narrative, regardless how tentative and even perhaps prone to oversight.”

If it is indeed a narrative, then we would benefit much from it by embracing its loose continuity. The looseness—not as a flaw in narration but a method for advancing the story into greater possibilities. I embrace the possibilities and take pleasure in looking at a Leonilo Doloricon painting representing domestic folk against Jose Tence Ruiz’s irreverence of the whole social structure, in David Medalla’s contrite assemblage against the purity of Robert Feleo’s sawdust sculptures, a Kidlat Tahimik video nestled along a Junyee installation, a group of Kuikok, Belleza, and Malang’s, right next to a group of Chabet, Albano, and Galang’s.

And finally, a note on the inclusion and exclusion of artists, and perhaps the reputational system in general: the exhibition is not a captured moment, but a representation of a steady movement. In defining the nature of a stream in motion, it is futile to ponder on whatever is caught between the ripples while trying to understand how the current flows.

The Philippine Contemporary is an understanding of the current moment in art, through the how’s and why’s of numerous possibilities to getting to where we are now. It has achieved a feat, as to what any committed Museum would strive for—to be able to bridge the gap between education and exploration.