As big institutions and galleries tremble and scramble to migrate online and ride the NFT bandwagon, I still yearn for a pause, a space to breathe, a place to grieve, an in-between, a headroom to pursue fundamental questions: What is art? What is art for? Who gets to make it? For whom? Where is it going?

The art world’s frames of pre-pandemic modes of creative production, circulation and care built around tangible forms and events, extravagant physical structures, individualism, tourism marketing and hierarchical relationships still need to be challenged and reimagined. Like rhizomes, Load Na Dito (LoNaDi for short) invites us to germinate and bloom in community and conversation.

“In times of crisis, artists should find the community, which will be their base and mission,” Load na Dito shares pages of Nicanor Tiongson’s article found in Kultura, vol. 4 on their social media on August 31, 2020.

Initiated by curator Mayumi Hirano and artist Mark Salvatus in 2016, Load na Dito is a homemade research project that confronts questions of participation and collaboration in contemporary art. “Load na Dito” translates into “Load Here” in English, but it’s actually a vernacular term for a local top-up system popularized by telecommunications companies in the Philippines. It’s rooted in our tingi or piecemeal culture, where we package products into little sachets to make them more affordable.

Developing the “sachet system” as practice, LoNaDi morphs and shapeshifts in changing contexts within their economic capacity without losing their own voice. LoNaDi makes projects in varying scales across different locations around the world, recognizing any space, whether virtual or material, as a site for knowledge and art to sprout and flourish. LoNaDi moves the locus of creativity from the autonomous, self-contained individual to a new kind of dialogical structure, breaking known hierarchies, underpinning the potency and value of interdependence and convergence.

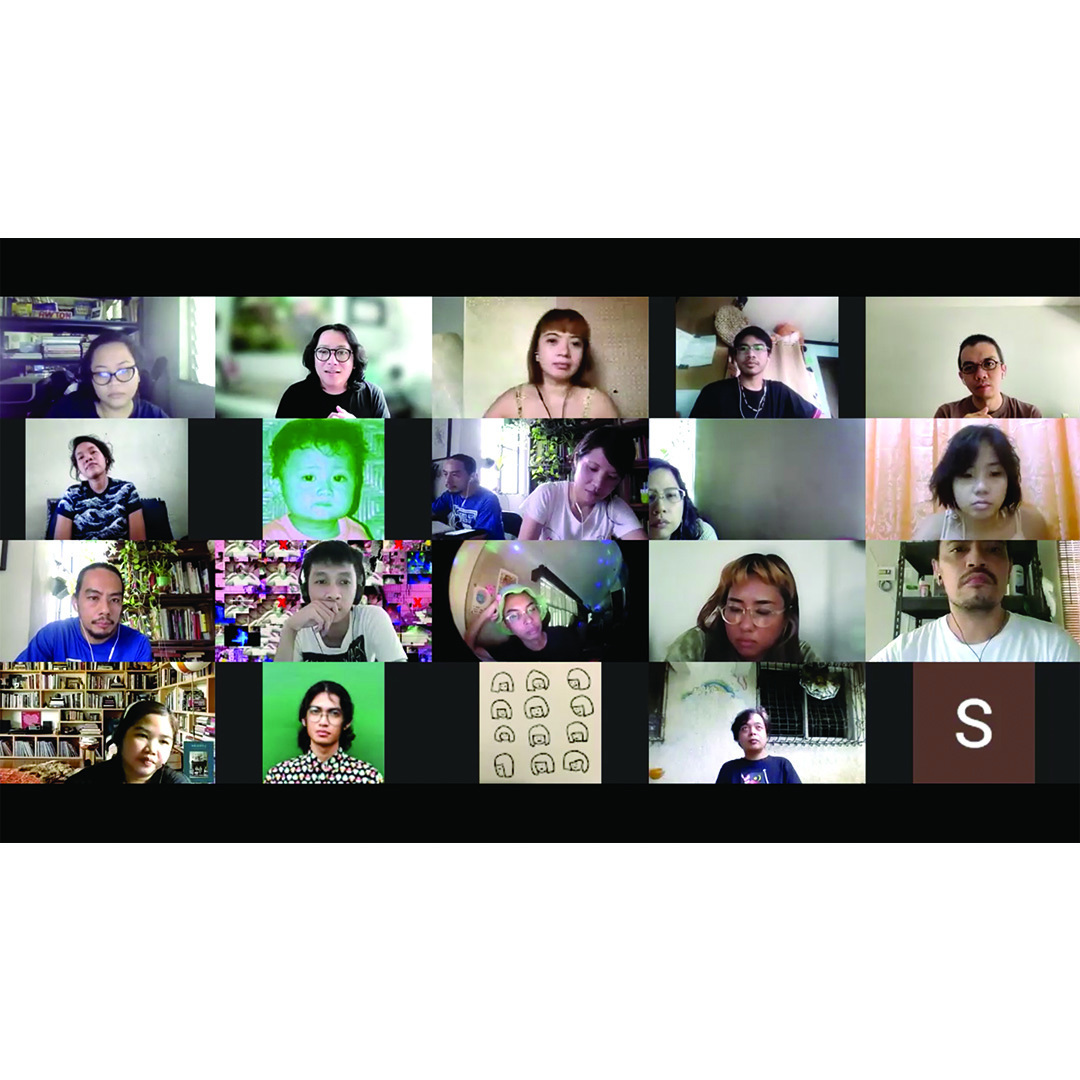

In the middle of the COVID-19 crisis, LoNaDi organizes the exhibition There within Here using Flex*—a card game the duo invented. The exhibition had no theme or curator. The participating artists Jed Gregorio, Miro Kasama, Yuri Kunimochi, Miki Murakami, Ayumi Nagato, Gerome Soriano and Tanya Villanueva just played Flex* regularly online. Despite being in different parts of the world, the exhibitors naturally developed a shared home, their own digital archipelago.

"The exhibition was formed by the links of intentions to receive such elusive presence,” Nancy Chen expresses in "Speaking Nearby: Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha” at Visual Anthropology Review.

LoNaDi’s description of the game brings to mind Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of the rhizome:

“Participants sit in a circle around an empty bottle in the center. There is no moderator; the game proceeds by spinning the bottle. The person pointed by the bottle picks out one word from the deck of Flex* cards or the previous person's talk and freely speaks about what comes to his/her mind triggered by the word. Although the content of the talk does not have to be related to what the previous person has said, the participants need to always keep their ears open to what others say because they never know when their turn would come. It is up to the bottle, which facilitates horizontal relationships among the participants.”

The rhizome is a process of existence and growth that doesn’t come from a single origin. Deleuze and Guattari use the metaphor to illustrate the difficulty of uprooting or destroying entities and collectives that don’t have any central provenance like mold or fungus, which can reproduce from any cell.

Similarly, LoNaDi pursues an approach with no boundaries or centers. It is non-linear, multitude and all-proliferating. LoNaDi is fluid and mobile, always with diverse elements depending upon the situation. It’s invisible and hidden underneath. It’s what remains unchanged as its spawns continue to evolve and mutate. LoNaDi forms a confluence of people, ideas and things self-organizing on their own.

In the same month, LoNaDi features 32 artists from the field of visual arts, comics, publishing, poetry, performance, music, engineering, film and activism in Pasa Load Online Residency. It was just hosted on Instagram (IG), making it accessible, intimate and free to publics across the globe. How LoNaDi describes the residency is a gesture of vulnerability in its purest form—an evidence of a new attitude and perhaps a vision of what’s to come:

“Using, sharing, passing the Load na Dito IG account as the space for online residency. Artists are given total freedom to do whatever they want. It is the space of production, presentation and viewing all in one.”

Here, the artist is the producer, curator and audience all at once. The residency exposes a conflict digital technologies bring where our current notions of art and the artist are constantly undermined and rewired.

Navigating the unknown future is a flow of energies, values and passions in Should I Stay or Should I Go? Supported by Koganecho Area Management Center, LoNaDi holds an open space for five art initiatives in Asia to look at their rearview to see where to drive towards. The discussions cover fluctuating processes, sustainability and adapting amidst precarity.

Focusing on facing and living ambiguities show how LoNaDi embodies a constellation of questions in this project. Art becomes an open-ended, ongoing conversation.

As I write my entry, Documenta, one of the world’s most significant art gatherings, is vibrating the current and future rhythm of contemporary art. This year’s artistic director collective ruangrupa centered the edition on the concept of the “lumbung”—Indonesia’s term for a communal rice barn. Meant to “heal today’s injuries, especially the ones rooted in colonialism, capitalism, and patriarchal structures,” this agrarian framework, where excess harvests are stored for the future use by the community, echoes LoNaDi’s culture of knowledge and resource sharing. It has nothing to do with Artificial Intelligence, digitization or cryptocurrency; it is economic and political, highlighting the social dimension of art.

Maybe this is the new lasting bedrock we need to bear fruits that never rot: a radical generosity and trust in dialogue and collective movement.