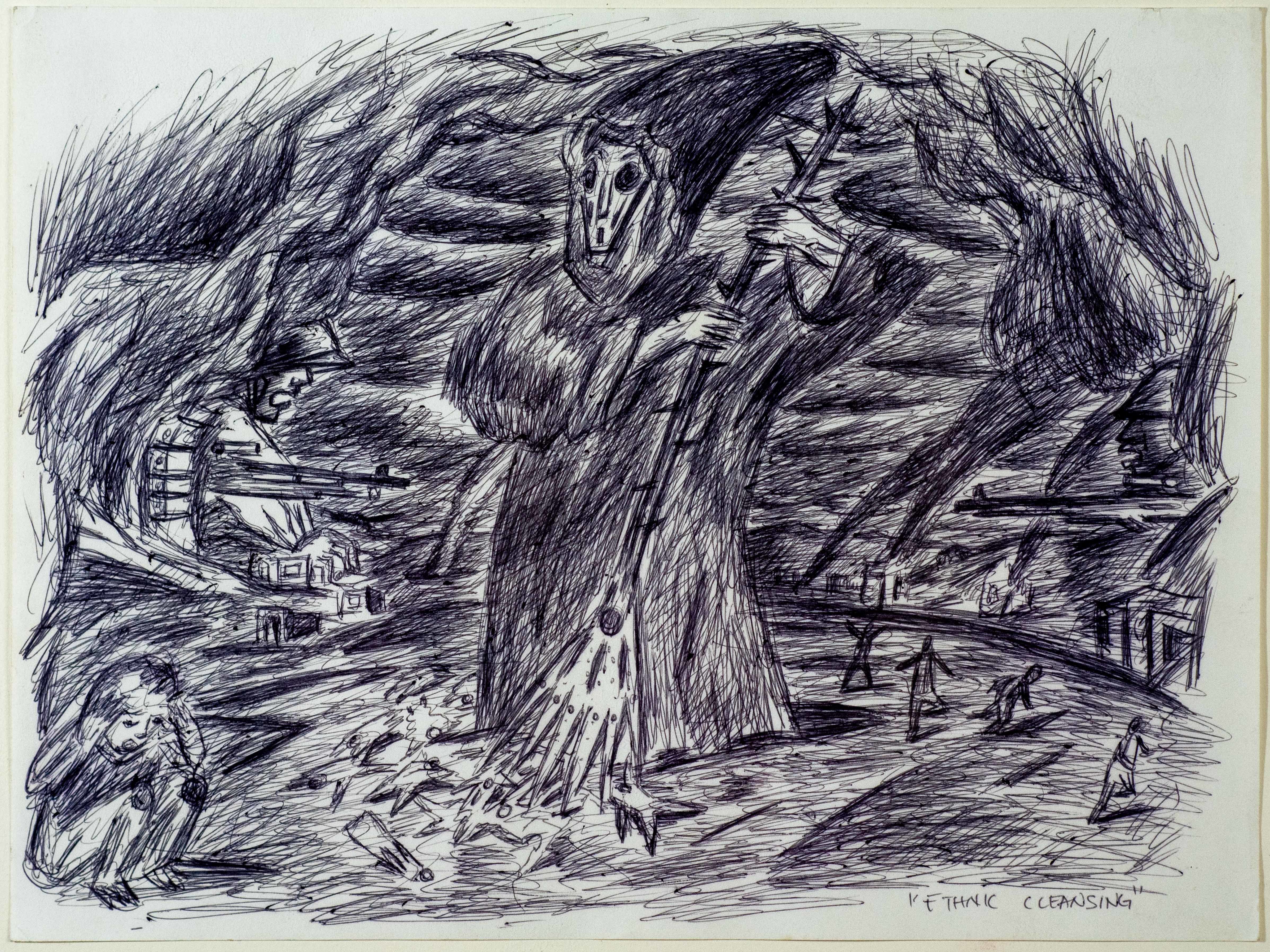

Has Charlie Co championed suffering? At the farthest back of his exhibition, in the Ateneo Art Gallery, is an ink-on-paper depiction of genocide. In it, a figure lords in the center, cloaked in the garb of plague doctors, dusting a massacre of corpses with a broom sinisterly resembling a hand of glory. Profiles of two soldiers sandwich the scene from both sides, artillery pincer attacking the center. Storm clouds hang above the people like halos. Tornados loom. The victims in the scene are puny and figureless, almost afterthoughts. At the bottom left a boy crouches, his youth left intact for our eyes to penetrate, his hands covering both sides of his head, as if to nurse the carnage away.

This drawing—Ethnic Cleansing—is, I think, one of Co’s many self-portraits: here, he is the harrowed boy, the killing spree entirely of his vision. The withheld date of completion marks a fascinating implication: did this dream of murders come to him so quickly that, in the haste of recording the scene, he had transcended the logical operations of time? Or is it the opposite: is the muscle memory of death so habitual to him that he drew the piece in the same casual gesture as breathing, finished, forgot it abruptly, and rediscovered it at a later date with a startled oh!? How can an artist depict nightmare so effervescently, and how does one convert the energy of suffering into art with much gusto, much grace?

If there is an artist whose hellscape is recognizable, surely it is Charlie Co’s. In the exhibition The World According to Charlie Co, Catholic images are reimagined just as much as human bodies are twisted, contorted, made alien. Crows metronome between pieces: in Days After, tweeting eagerly by a bedridden man’s side; and in Caliphate, a crow-messiah looms kingly over a masked mob, the tip of their spears kissed with fire. Though often desolate, Co’s landscapes are coated in a childlike palette: in the painting A Year After, for example, his empty desert is summer-bright, pearly ruins ebb in the heat waves, and the sand glows with the healthy shade of citrus.

We might find it uneasy to be voyeurs of faraway suffering—an effect we should continue to cling to—but suffering, through Co’s art, is articulated, made mutable. Critic Susan Sontag says finding episodes of “beauty” in the photography of the pained may seem heartless, “but the landscape of devastation is still a landscape.” In Co’s world, his cast often play ambiguous roles (the plotting women in The Chosen One, or the unsure lovers in Keith House Sydney), but the torment of his protagonists takes center stage, often cased in the veneer of a boy’s dreamscape, and their discord toes the shores of beauty: in an untitled oil on pastel painting from 2019, for instance, we see a man surrendering to the bathtub. His skin is so crimson it seems bleeding, but so are the lilies showered around him.

Co himself plays pained versions of his person. In 2013, when his diabetes had gotten so severe he needed a kidney transplant, he painted a quartet of self-portraits, each depicting epochs of his medical journey. In the first one, Co comes to us darkly: standing, donning his apron to signify his position as artist, his skin tarred like the atmosphere of uncertainty he unleashes around him. In the second self-portrait—sat on a wheelchair, apron off—a little life returns. There is gloom in his sunken eyes, but his skin is the golden-yellow of Eastern philosophers, and his right hand is slightly raised, as if to unearth the secret stuff of nightmares. On the Fifth Dialysis, the next installment, depicts Co reddened demonly from surgery. In the fourth of this series, completed 2014, called Last One, we see a figure in a patient’s gown, his head low. It is tautological to assume it is another self-portrait, but we hesitate: the figure is so obscured in his torment he seems no Charlie at all. Wisdom and wit seem siphoned out, but here is Co; pained, yes, but radically changed, persevering.

It is easy to tape over Co’s exhibit and label it as another portal into nihilism, but I think this is an unchallenging write-off; Co combats and parries nihilism. He befriends his devils. He appears to us not as a man dying but a man living despite everything. In a flat lay of four crucifixion paintings, all untitled, Co performs an alchemy of suffering: where, beginning in 2008, the St. Sebastian-like figure of a man is crucified, muscled and crowned with thorns, but as the paintings continue chronologically, the life in him dispels. The crucified by 2023 is dying, wrought with agony—puncta the white of gritted teeth constellate his body—but the landscape behind him—the green of grass, the burgeoning fruit from trees, the sun—becomes alive. Suffering is unavoidable phenomena, and by no means is it always good, but it can be used, and we must use it, to transform.

We might describe our experience within Co’s universe as an exercise of sympathy, but I think this description is fell. Sympathy is a cutlass used too profusely to carve positions of our innocence and impotence that, by this point, its sheen has dimmed. If deep feeling is stirred by Co’s art, then we must begin to act on it, lest it turns into passivity. Sontag offers us a warning: “It is passivity that dulls the feeling.” Charlie Co shows us his demons, his horrors, so that we may remember how beautiful our life can—and should—be, and if we act and revolt in pursuit of this beauty, with the stubborn poise wild boys have, then perhaps we should be fine. I keep wanting to revisit the hellscape where Charlie awaits sagely for company; I want to meet his misery with mine.

Works Cited:

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others, Picador, 2003.