Filipino-American artist Pacita Abad was born in the coastal province of Batanes, a juvenile witness to Mother Nature’s tendency to be at once a divine source of terror and comfort. The province is remote, beset by natural disasters yet bestowed with lush greenery and flourishing wildlife. It’s likely that the island’s relative isolation coupled with these polarizing conditions necessitated Abad’s nomadic tendencies, fostering in her a desire to see as much of the world as she could.

As such, Abad traveled to the US to study law after earning a degree in political science, but decided to trade politics for paintbrushes and pigment, jumpstarting a 30-year painting career spanning 6 different continents and over 50 countries, whose diverse cultures and landscapes became a perpetual source of inspiration throughout her practice.

Abad is most known for her “trapuntos,” meaning “quilted” in Italian. Inspired by African and Melanesian tribal art, and hand-made out of swathes of fabric, painted, embroidered, and adorned with beads, sequins, and shells, these canvases serve as a tapestry of her travels. In keeping with Abad’s wayfaring ways, many of them reside in various corners of the world. But recently, several trapuntos made their way back home to Abad’s native Philippines and into De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde’s Museum of Contemporary Art & Design (MCAD) for an exhibit titled A Million Things to Say.

The show is anything but a mere retrospective of Pacita Abad’s staggering oeuvre: one piece, from which the exhibit takes its name, displays her signature circular patterns, another is plucked straight from her “Immigrant Experience” series, but neither take center stage. Curated by MCAD director Joselina Cruz and Abad’s London-based nephew Pio Abad, the exhibit instead aims the spotlight at Pacita herself

MCAD is the perfect venue to commemorate Abad and her labors of love. The museum’s lofty ceilings andbleached, bare-bones interior punctuate the vibrancy and intricacy of Abad’s hand-stitched, hand-painted canvases. Her trapuntos come to life: suspended from the ceiling, they appear to float. The effect is mesmerizing, with some canvases as high as 10-feet tall towering over the viewer. The arrangement also allows for a thorough examination of each work from front to back, revealing the meticulous craftsmanship that Abad dedicated to each piece.

The pieces from her Underwater Wildernessseries benefit most from this set-up. To view them, one lithely weaves in and out of strategically placed canvases, as though they were swimming, which is appropriate given its subject matter: Abad turned to the prosperous marine life of her province and the underwater landscapes she encountered during her many diving trips across the Philippines for inspiration.

My Fear of Night Diving: Assaulting The Deep Sea (1985) is particularly arresting, depictingan entanglement of underwater flora closing in on a shark and an octopus caught mid-brawl. The scene harkens back to J.M.W. Turner’s paintings of life out in the perilous sea. It’s one of Abad’s darker pieces that showcases her versatility as an artist.

Flanking the museum’s entrance are trapuntos from her Masks and Spiritsseries. Inspired by her travels to far-flung locales such as Congo, Haiti, and Sudan and her interactions with local tribes people, the series was born out of Abad’s desire to challenge Western and neo-colonial perspectives that situate “primitive” art as “low” art and dismiss hand-stitched fabric as mere “craft.” Abad turned these ideas on its head.

It’s not surprising that her encounters with indigenous tribes resonated with her so deeply: the artist herself is from the Ivatan tribe of Batanes. Masksemploys the iconography of primitivism and makes use of locally sourced materials; it is a celebration of tribal culture and native traditions that mirror Abad’s love for her own heritage.

On the wall adjacent to it are quotes from Abad about her craft, in one panel she says, “I have always been hard to classify, and my work is an extension of me. People are always trying to put things in neat little boxes. My work does not fit in any of these… I am not concerned about where I fit in and do not fit in.” It’s possible that these masks reflect her refusal to be pigeonholed, as both an artist and a human being

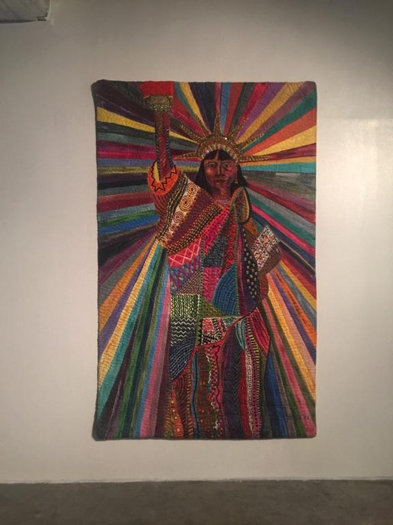

Abad’s trapunto masks reclaimthe plurality of identity, transcending the various “masks” she must put on in her everyday life: that of a Filipino, an artist, a woman, an activist, wife, immigrant, and citizen of the world. This theme is further explored in LA Liberty(1992) located in the mezzanine, featuring a woman with dark brown skin portrayed as Lady Liberty. The piece echoes Abad’s own identity as a Filipino-American and disputes the concept of freedom in a country that is notorious for racial profiling against dark-skinned folk.

It is both promising and unfortunate that Abad is the first and only woman to be granted a solo show at MCAD. That three men have already had solo exhibitions mounted at the museum before her is a symptom of a larger systemic problem, but her inclusion is still an indicator of change and it arrives at a most opportune time when notions of womanhood and being a woman of color are under attack. Abad is an emblem of resistance for the modern Filipino woman.

Ever attuned to social ills, Abad often depicted the women and people of color she met during her travels in her art, in the hopes of communicating their respective experiences of being treated less than fairly. But in this exhibit, it is Pacita alone who is given a share of the limelight. The exhibit examines her art parallel to her various identities: as an intrepid explorer, a woman of color, a social activist, and so much more. Yet not even the entirety of her 5,000-piece body of work can begin to scratch the surface of her being. Because for the million things Pacita Abad wanted to say, there are just as many things that Pacita Abad was and wanted to be.