There are two things we must know about Pacita Abad’s A Million Things to Say, now on exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD). First is that the exhibit is billed as a “reintroduction” rather than a retrospective of the artist. Second, in MCAD’s decade long existence, this is the first show headlined by a woman.

It’s curious how these two pieces of information are tied together. By not calling it a retrospective, the circles and wayang puppets that Abad is known for are absent. Both the museum’s curator and the show’s co-curator, Joselina Cruz and London-based artist Pio Abad and Pacita’s nephew, underscore the importance of what it means to be a global contemporary artist. Global suggests that the artist has an awareness of what happens in the wider sphere of things. Something that is abetted by Abad’s lifelong experience of travel. First as an activist student sent to San Francisco by political parents, to study law and to avoid the long arms of a would be dictator. She then meets and marries Jack Garrity, with whom she spent a year hitchhiking from Istanbul to Manila. Her husband’s work as a diplomat with the World Bank would then take them around the world, mostly in developing countries, which informed her early art that depicted social realist scenes.But we see none of these paintings.

Instead, when one enters MCAD’s cavernous space, one is met with the gigantic masks from Abad’s Masaiand Bacongoseries suspended from the ceiling and held up by metal rods, and done in the trapunto technique that Abad has developed throughout a career that spans more than three decades.

Trapunto means “to quilt” in Italian, coming from the Latin word pungere,meaning to prick or to pierce the fabric. It’s a method of quilting that uses two layers of cloth, usually cotton canvas with stuffing in between. It is then embroidered with running stitches, embellishments are added. There is precision in Pacita’s technique. While her works are larger than life and flowing with color, when one looks at the back, one can see the neatness of the stitches. Her masks are remarkable in that she did not work from studies, as her nephew Pio attested. She worked directly on the canvas, with intuition, but always with precision. The backs of the works are as interesting just to see how this mind, while seemingly freewheeling, was actually focused with the singular display of craftmanship.

Pacita Abad’s works make use of rickrack, buttons, sequins, fabrics like ikat and batik, and in one painting, even a flattened aluminum tube of paint. Her underwater series, like in Puerto Galera at Night, the branches of the corals use of beads often seen in necklaces, little mirrors stitched on the canvas refract sunlight coming in from several hundred feet above the water. But in the hands of Pacita Abad, trapunto becomes three dimensional, almost a kind of sculpture.

Moving from Abad’s figurative works at the entrance to the more abstract works in her later years at the back of the first floor of the exhibition, one is awed by the expanse and talent on display. Why then did MCAD take ten years to feature an exhibit headlined by a woman. One can’t help but think of that question posted by Linda Nochlin all those years ago: “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” It’s a question that even the fashion world asked recently, when a shirt in the Spring/Summer 2018 collection of the House of Dior asked that same question. For the first time in 70 years, Dior finally had a woman creative director, Maria Grazia Chiuri, who sent a shirt to the runway last year that “We Should All Be Feminists.” There was a controversy, similar to this year’s question. But really, seventy years or ten, why are our institutions only recognizing female talent now?

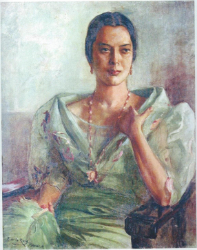

In the case of Abad, her piercing of the grand male tradition of great artists go back to 1984, when she was the first woman to be given the Ten Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) award. Artists, older and younger, all men, are questioning an award given to a rather privileged young woman of color, an Ivatan from Batanes, who travels the world footloose and childless with her husband, and yet, if she were male, wouldn’t she be celebrated for her dedication to her art?

In the second floor of the museum, Abad’s version of the Lady Liberty raises her flame to the world. Alongside the artist’s timeline from her birth in Batanes to her death from cancer in the early 2000s, there is an interview with Felice Sta. Maria that starts innocuously enough. “What is your ideal working space?” the interviewer asks. Abad answers that she works wherever she finds herself. Sometimes in a small space, sometimes in a hotel room. She makes whatever space she finds work. Sometimes, her mother and sister helps her sew.

Then comes the question about the “life cycle” of a woman. Essentially the interviewer is asking: At what point in an artist’s life should she work on having a family, fulfilling the traditional female role of motherhood? Isn’t that important to a woman too? We come to a realization that perhaps women of Pacita’s generation, like the interviewer, were tied to notions of femininity and what it means to be a woman. Yes, you’re a very prolific artist, but shouldn’t having a family and children be on your agenda too?

Pacita smiles this quiet smile. Down the hall, she stares back under the yellow glow of the flame in L.A. Liberty. Downstairs, near the entrance, after the masks, Pacita is sailing away from time, the waves carrying her downstream to a time when the descriptive “woman” is not important, there is only the artist.