Inspired by Southeast Asia’s and the Philippines’ history of opulence, Ayala Museum’s Gold In Our Veins by artist, designer, and taste-maker Mark Lewis Lim Higgins tells the story of “a re-imagined antiquity through a series of 30 portraits inspired by the ancient histories of Indochina, the East Indies, and the Philippine Archipelago” (Ayala Museum). Higgins’ mixed-media paintings feature noble men and women surrounded by a fusion of several elements such as flora, ornaments in gold, ancient script, and sacred symbols.

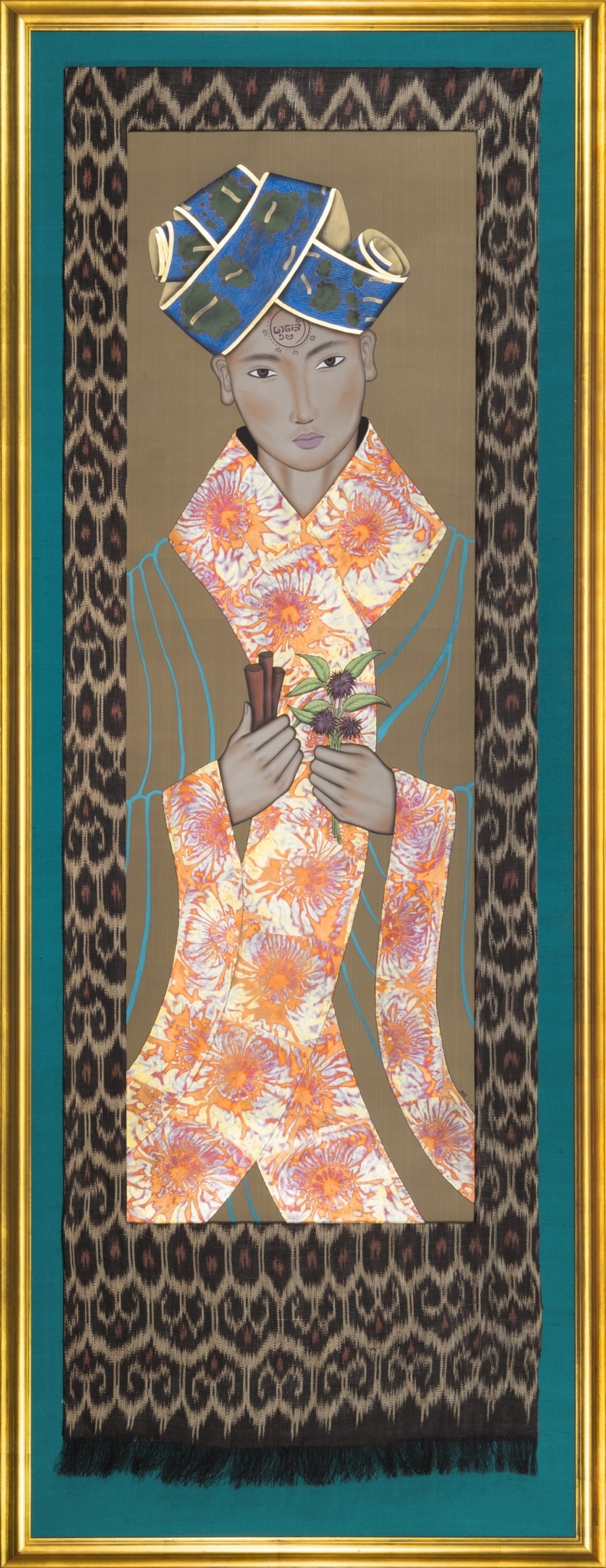

The painting Caiumana (2015) greets the viewer at the entrance of the gallery. In the illustration, a nobleman is holding sticks and flowers of cinnamon. His headdress is lined by a scroll which depicts the maps from Antonio Pigafetta’s manuscript Report on the First Voyage Around the World (c.1550). Towards the end of the entrance hall is the painting Angkatan (2015) where a noblewoman is holding a manuscript with calligraphic detail from the Laguna copper plate. On top, a funerary mask in gold is flanked by rice gods or bul-ul, and at the bottom are the cycles of the moon.

As archetypes, these portraits enliven the symbols that embellish them with their meanings and stories from different Asian countries and periods. Of this exhibition, Higgins shares: “Far beyond the limits and borders of what became countries or nations, we are all maps of our ancestors. This is my tribute to the gold that flows in all of our veins” (Ayala Museum).

As both artist and curator, Higgins, with the creative output of scenographer Gino Gonzalez, elevates the visual experience of his mixed-media paintings by converting the museum’s gallery into an early 20th century Chinese warehouse showcasing alongside paintings actual artefacts and antiquities connoting a variety of imagery found in Asian antiquity. Higgins himself selected these artefactual evidences of Philippine archaeological gold, indigenous textiles, and Chinese and Southeast Asian trade ware ceramics from the Ayala Museum collection.

For example, a Chinese blue-and-white jar depicting The Immortals of Chinese mythology is displayed in context with a pair of paintings entitled Chenla (2017). The male and female portraits share similar blue-and-white designs on their upper garments—the former with floral, cloud, and avian motifs, while the latter with ocean wave and repeating twin fish patterns. The gold mask illustrated above the noblewoman in Angkatan (2015) is in itself from the Gold of Ancestors exhibit.

At best, the exhibition as warehouse provides a sensory experience: one can almost feel the textures of textiles, smell the scent of herbs like ylang ylang and cinnamon, all neatly arranged around the space. Inside, you can hear a man chanting in a language both familiar and foreign. And as one exits to the end of the warehouse, he or she is immediately transported back to 2019.

It is not uncommon for art exhibitions to have actual objects from the museum displayed in ways other than its established institutional contexts. Curatorial projects such as this call back efforts of intervention to the museum’s display and function, such as Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992) at the Maryland Historical Society, and in the Philippines, Annie Cabigting and Nilo Ilarde’s self-referencing Museum Watching (2018) at Finale Art Gallery.

What makes Ayala Museum an ideal setting for this imagined-yet-constructed sensorial time-warp is its being a history museum – always influx between history and contemporaneity, the museum straddles the role of a compendium marrying both accuracy to history and new expressivities of this history, all while aiming to attract the widest net of visitors and knowledge-users as possible. Here, the curatorial meets audience development. According to Allison Hart in Sensorium, Compendium (2015):

Only museums mix a detached, one-level-removed kind of historical narrative (informational, textual) with a narrative of continuation and presence, buttressed by very much “alive-looking” presentations and performances – such as replicas, full-scale historical backdrops/environments, etc. – with ideally immersive and transportive functions. The museum transports, is transported, existing simultaneously in both present and past

In the case of Gold In Our Veins, Ayala Museum becomes a liminal space, a heteropia as Focault coins, where the temporal, mental, and physical exist in a single representation. As the gallery is converted into a sensorial time-warp of an opulent “Southeast Asia”, the museum acts as a counter-site where all these symbols are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted.

By intervening on the museum collection’s inherent contexts and bringing them into an imagined space and time, Higgins opens the exhibition to the reinterpretation of his art and the museum as an institution. On one hand, a visitor might feel empowered to create their own experiences through the seduction of imagination. Yet on the other hand, some may unconsciously reproduce assumptions embedded in the ways by which they are Other—distanced from themselves in space and time.

What really results in the exhibit’s layering of meanings of archetypal portraits symbolic of Southeast Asia, their installment in a sensorium of sights, sounds, and smells, the re-configuration of a historical narrative using actual evidence, and its construction in an imagined space and time within a heterotopia— is a vortex. Everything is here, almost literally. In a way, history might appear to us in a similar manner: it is much more complicated than linear timelines and chronological events as evidenced in the Dioramas of Philippine History (1973) in the same museum. Higgins says in an interview: “This is what Southeast Asian art and what Philippine art would look like from my perspective, it’s not necessarily a conclusion but a meditation.”

Like a meditation, history might come as intuitive messages, or even personal ideas that represent the sublime. In the case of Gold In Our Veins, the idea is really opulence. Indeed, Southeast Asia’s wealth is deep-rooted in the objects and meanings Gold In Our Veins presents. Yet we also find that the greatest treasure is our complex hybridity, and how these ideas connect us all.

References

Hart, Allison. "Sensorium, Compendium: The History Museum, the Human Scale, and Creating Meaning." Academia.edu. April 2015. Accessed May 2019. https://www.academia.edu/15157137/Sensorium_Compendium_The_History_Museum_the_Human_Scale_and_Creating_Meaning?auto=download.

Johnson, Peter. "The Museum as Heterotopia." Heterotopiastudies.com. May 2015. Accessed May 2019. http://www.heterotopiastudies.com/the-museum-as-heterotopia/.

Foucault, Michel. "Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias." Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité, October 1984. Accessed May 2019. http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/foucault1.pdf.

Crosby, Nicolas. "In Search of Heterotopia: Immersive Experiences in the Museum." Digitalcommons.cwu.edu. November 2016. Accessed May 2019. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1598&context=etd.

Collin, Armand. "Key Concepts of Museology." ICOM.museum. 2010. Accessed May 2019. https://icom.museum/en/ressource/key-concepts-of-museology/.

Ramirez, Eileen. "Making Tracks: Curation as Frame and Coding." Academia.edu. 2011. Accessed May 2019. https://www.academia.edu/24914610/MAKING_TRACKS_CURATION_AS_FRAME_AND_CODING.

"Gold In Our Veins: Mark Lewis Lim Higgins." Ayalamuseum.org. Accessed May 2019. https://www.ayalamuseum.org/2019/02/19/gold-in-our-veins-mark-lewis-higgins/.

Nadal, Nana. "“We Did Not Necessarily Only Become Civilized upon the Arrival of the West”." News.abs-cbn.com. May 2019. Accessed May 2019. https://news.abs-cbn.com/ancx/culture/art/05/19/19/opulence-and-wealth-abounded-before-the-arrival-of-the-westerners-as-proven-in-gold-in-our-veins.