When did the notion of ‘community’ begin to figure as a sort of moral guarantee? Once artist statements, project proposals, and bionotes throw in this term somewhere in their writing, a writ of artistic altruism is automatically presumed—and all right to scrutiny is simultaneously disavowed. After all, it is in its engagements with the broader world that art can potentially emerge as its most emancipatory: as a liberating, or at least an ameliorative, force amid contexts of injustice. However, we must recognize that the juncture of art and community lies at a fertile yet slippery terrain; and to tread on this carelessly risks endangering the same people whom it seeks to support.

My questions were prompted by Vien Valencia’s BAD LAND, whose first exhibitionary iteration was mounted last April to May 2024 at Underground Gallery in Makati. Valencia described the project as an ongoing collaboration with a Badjao community in Manila, where children from the group were given cameras to film daily scenes of their urban life.

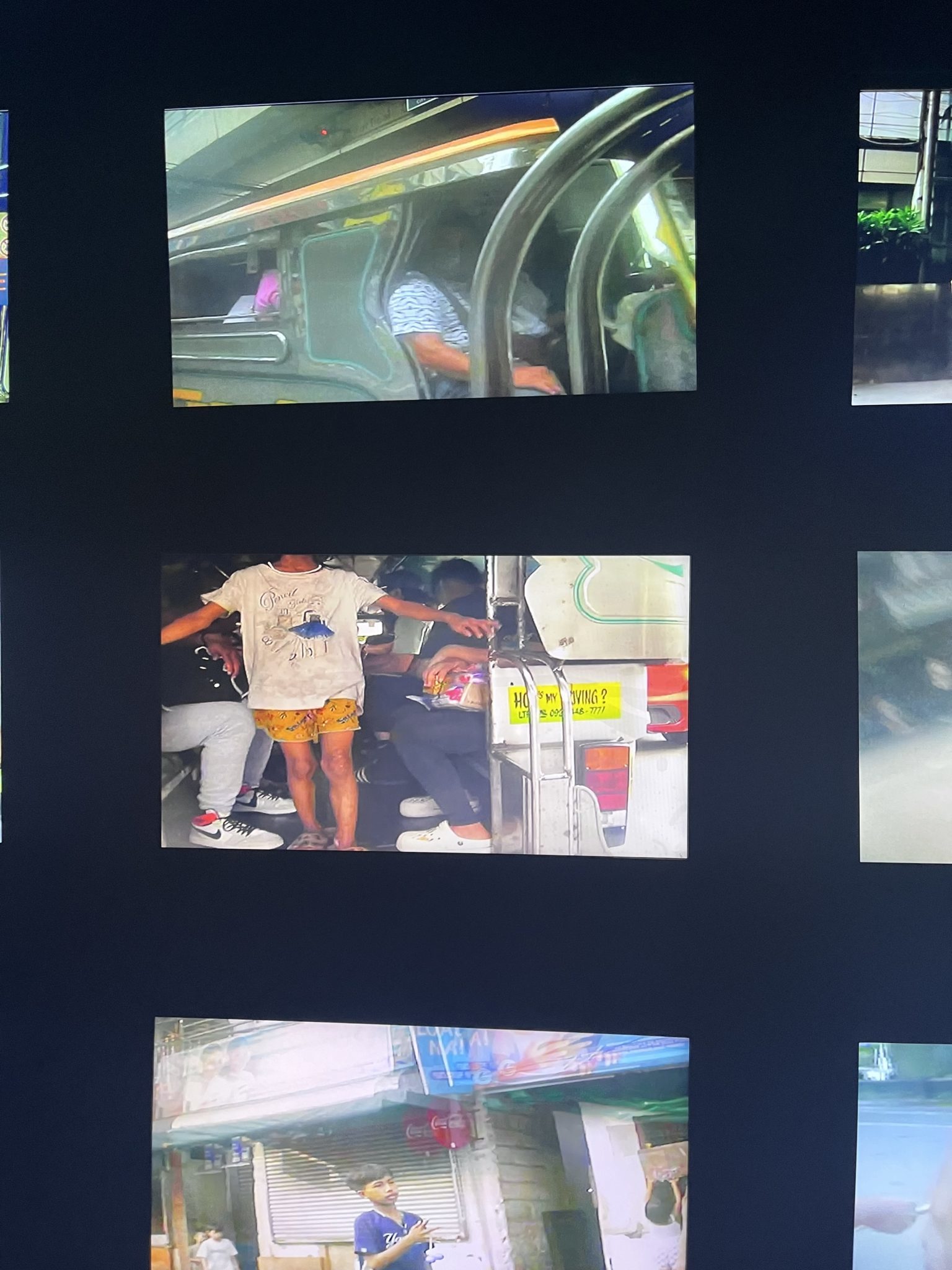

The output occupied two rooms of the gallery. In one blacked-out room, the lone source of light is the project’s centerpiece: an entire wall of 84 (arranged in 7 rows and 12 columns) shaky and disjointed video clips shot by the children. The videos show them, among other scenes, climbing jeepneys to seek alms, carrying younger siblings as they hand out containers and envelopes again to seek alms, or conversing with the camera in vlogging fashion. All this footage was played simultaneously in what emerged as a barely decipherable visual and sonic unrest. Meanwhile, the other room comprised dozens of woven textiles laid out to overlap across the floor. No contextual background was provided, so we were left to assume how these textiles tie in with the rest of the show.

BAD LAND joins the rest of Valencia’s works described by the artist through the terms of ‘community.’ I locate it within the scope of community-engaged practices: projects generated in the context of art-making reliant on the engagement of particular communities. Such groups are often identified as outsiders to the arts ecology, often disenfranchised from the wider society. Their engagement typically materializes in methodology (e.g. ethnography, interviews) to create a model of production often perceived as participatory, collaborative, or collective (Bishop, 2012; Kester, 2005). In the Philippines, other artistic gestures that draw from community-engaged frameworks include the Emerging Islands residency and Martha Atienza’s long-time work with a fishing community on Bantayan Island.

In American and British art contexts, critical perception of these projects tend to dwell on their ethical ramifications, leading art historian and critic Claire Bishop to lament criticism’s ‘social turn’ at the expense of aesthetic appraisal. In other words, community-engaged projects are often evaluated for “the degree to which artists supply a good or bad model of collaboration” rather than for aesthetic considerations (Bishop, 2012, p. 19). The ethical and the aesthetic are perceived as binaries, with one usually taking precedence over the other in critical thought.

But parallelisms cannot be drawn to the Philippine context. When it comes to community-engaged works in the country, what is observed is the marked absence of criticism in its entirety. Projects that make the slightest reference to community, participation, collaboration, and other terms within this ambit are quicker to gain praise than scrutiny even when they make no mention of the ethical model by which they operate. No one questions the artists about ethics, in the same way that artists do not take initiative in discussing the subject. It is as if intentions—expressed in the artist statement or project proposal—are enough; how the intentions actually materialize is not appraised.

When Valencia’s BAD LAND was first announced on social media in 2023, it immediately garnered affirmative comments—often praising the “collaborat[ion] with a Badjao community” as a “beautiful” and a “great idea” (Vien Valencia, 2023). I wonder how it was so quick to earn acclaim sans any information about its context of production. From the artist statement, BAD LAND read as an attempt to help the Badjao children reclaim their own lenses and narratives. With the children now wielding the camera and directing its vantage, they held the potential to subvert the hegemony of the gaze of documentary producers, media sensationalists, and other opportunists who use their plight and culture for personal gain.

However, holding the camera does not guarantee control of the narrative. Scholarly studies that have used similar participatory photography methods as BAD LAND’s have shown that these techniques do not erase the preexisting terrain of power that encloses both researcher/artist and community (Abma et al., 2022; Prins, 2010), such that the community can still remain as ‘objects’ of an external gaze and agenda. These show how engaged practices are not exempt from concerns on surveillance, invasion of privacy, or unfair collaboration practices—a fact more urgent with groups who are already vulnerable as it is.

This is not to accuse Valencia, as well as other artists of the practice, of ethical oversight. Nor to urge against the adoption of these community-based processes when they hold so much emancipatory prospect in their capacity to represent, as truthfully as possible, the interests of the collaborating community. This is rather to point out that it is in the transparency of the ethical that community-engaged projects can successfully realize their potential. To caution against the descent of ‘community’ as an empty buzzword.

Ethical skepticism must be dispelled—and demanded to be dispelled—if we wish for both artists and critics to be conscious against reinforcing power structures in this arts ecology so rife with divisive tendencies. In contexts of flux, community-engaged practices stand among art’s most potent responses—only, and always, with the right exercise of caution and care.

References:

Abma, T., Breed, M., Lips, S., & Schrijver, J. (2022). Whose voice is it really? Ethics of photovoice with children in health promotion. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21. Doi.org.

Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. Verso.

Kester, G. (2005). Conversation pieces: The role of dialogue in socially-engaged art. In Z. Kucor and S. Leung (Eds.). Theory in Contemporary Art Since 1985. Blackwell.

Prins, E. (2010). Participatory photography: A tool for empowerment or surveillance?. Action Research, 8(4), 426-443. DOI:10.1177/1476750310374502

Vien Valencia [@vienvalencia]. (2023, June 23). Collaborated with a Badjao community in Manila for a moving image project [Photograph]. Instagram.com.