For my father who biennially arranges the town's pabasa, examining the image is protocol. Naglalakad-lakad iyan, he elucidates when asked why San Jose de Navotas sported a sombrero on his back. Gumagawa ng bahay at kung anu-ano. He knows what Joseph, patron saint of workers, has come to represent: the labor, toil, and industriousness of the townspeople. Days before Palm Sunday, he had invited old contacts to dismantle the saint's shield and swab its insides. Garbed in a full regalia of copper veneer furnished with silverwork and jewels, the dress—worn during its annual feast day parade—serves two purposes: to array San Jose so that it overawes its watchers and to safeguard the timbered image which it encases. Sometime after Navotas had been established as a separate town in 1859, the image was carved from the same molave wood of Malabon's San Bartolome and La Inmaculada Concepcion. It would remain forever bound to an outside kinship. Once its metal sheath had been dismantled, it was astonishing to find that like its fraternal siblings, it was painted in a somber analogous polychrome of green, yellow, and orange in the Iberoamerican iconographic tradition of Joseph. Donning hat, tunic, cloak, and sandals, San Jose displays a mobility depicted in pictorial conventions of the "Flight into Egypt" where Joseph pilots Mary and the infant Jesus away from death and into safe territory. Moreover, when 19th century Manila and its environs were plagued with epidemics, San Jose became emblematic of good health and a peaceful death. My father took a photo of the year 1872 inscribed on the copper. Tita Imelda, his eldest sister, shared a striking account: in the past, tubig ulan was collected for disinfecting the image after procession while a pulang bato was used for encarnacion (fair skin furbishing). Rey, a devotee, added that this type of cleansing was essential to protect against the habagat's harmful blow. But even as its material intimacies had been conveyed, the image was cached in 2020. In this age, to painstakingly wrap the body and sanitize one's flesh against an invisible agent have become requisites for welfare. The quarantine's further provisions came into play when San Jose's basket of tools was purloined, foreshadowing the pressing crisis: how now could the obrero make and amble?

Even before image and art had lost their performative and venerative spaces during the pandemic, exhibitionary infrastructure had been slowly nestling into the web. In 2020, museums, galleries, and artist-run spaces poured all their effort into this virtual expanse. When in November I found myself on Flickr searching for pictures, I came across the old Tinajeros bridge of Malabon. There appeared other photos of the Navotas-Malabon river, the church of San Bartolome, and wells and nipa houses at the turn of the century. Later I stumbled upon a photo of the 1949 high school class of St. James Academy Malabon culled from the Maryknoll Mission Archives in New York. Today's modes of transmission allow photographs to fall back to their subjects without warning. I peered at the photo and upon closer inspection found my young grandmother, Remedios, in the middle row, second from right, concentratedly gazing back at me. Images, especially of the past, like contagions develop remotely, circulate inconspicuously, and in the sudden point of contact, conceive symptoms of fever. Whereas before the outbreak, virality had become paramount in the spread of images, the archive now adjures a measured diffusion of material demanding history to flood into a post-pandemic resisting extinction and fighting for life. When pursuits of motion, creation, and exhibition are stunned by a virus, the archive approximates its circulation. Artists revisited their personal reserves while institutions allocated their budgets to cataloguing and digitizing their resources. The past and its references attend to a present crisis of an unimaginable future.

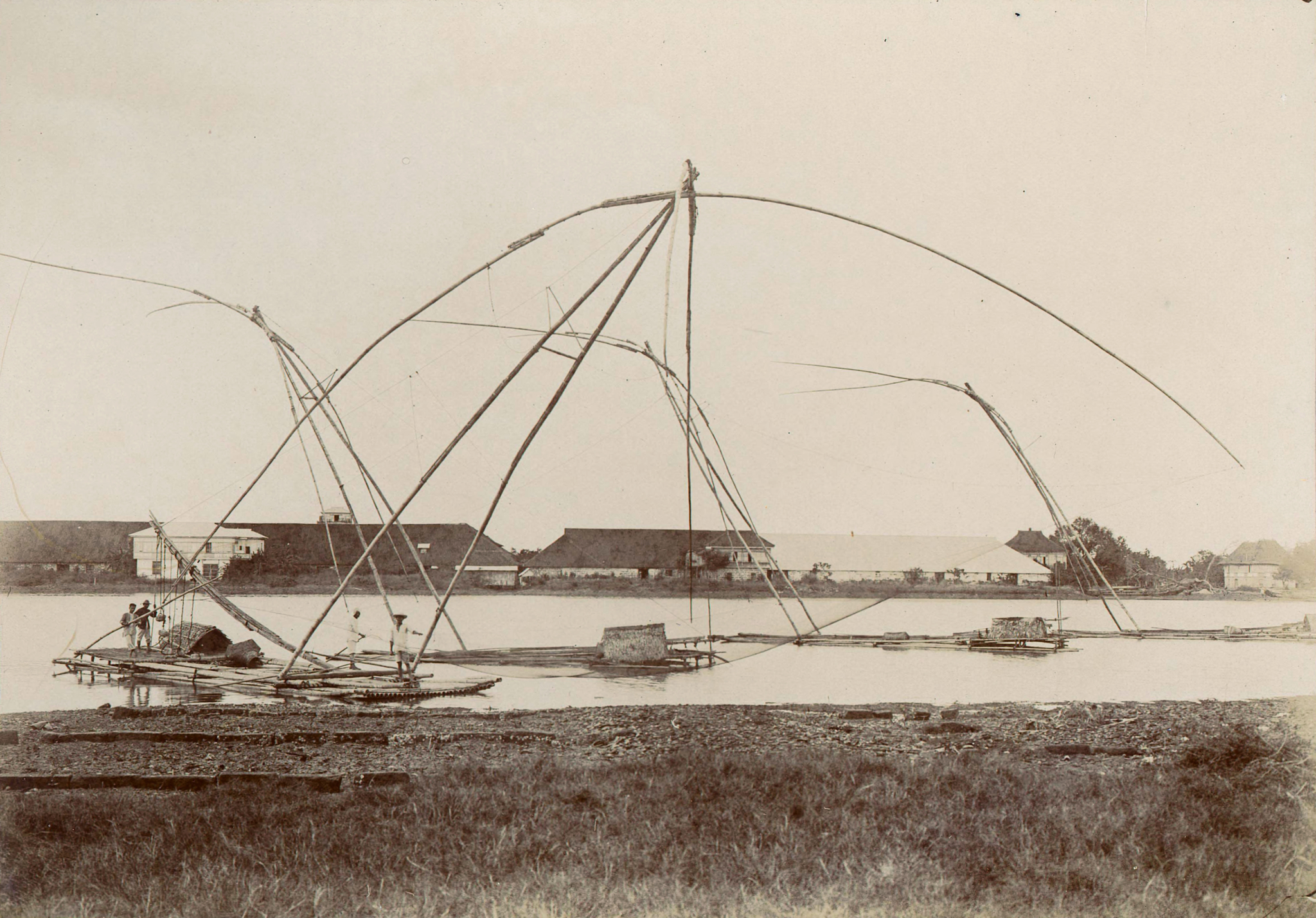

Once borders were imposed all over the world, I paid close attention to our house where in the 90’s, one had to descend through a driveway to get into the looban and arrive at the river. Old residents of Navotas know that the colossal reclamation projects of the 70’s around the port area caused a rise in sea levels. While the perennial dredging problem occasioned the river's demise, the island is now being engulfed by the tributary that once separated it from the continent—its isolation has caused its foundering. A narrow islet that stretches 3.5 kilometers or so, one could walk Navotas from end to end in just forty minutes. It was named so because what was once adjoined to Malabon and Tondo broke away when a water channel pierced the land, altering the area definitely. It was separatist as it was steadfast to esteem its geographic separation and remain immune to the mainland, because in the mid-19th century there were no bridges spanning the river and the people found it difficult to carry out affairs of trade and worship. Today people of the arts find themselves in a similar predicament of remaining insular while bridging cautiously into the social peninsular. A friend who is an artist intimates the limbo lucidly: Ang hirap mabuhay, pero 'di ko nais mamatay. A decade ago, my father laid volumes of small rocks of about five feet in height around the house to raise the ground and leave the structure’s base to sink. When the river appears to be dead but closes in on the domicile, how can one reactivate the aquatic border so it could hedge the island in but not cloister it totally? Artists move, just as Joseph does, to seek out life. Archives circulate images to extend their aliveness. The stagnant yet swollen river of Navotas-Malabon cues resuscitation from inertness. When it was reported in 2020 that freeways would soon be built over Navotas, for a moment I entered an early adulthood memory of a white migratory bird flying over a nearby fishpond. To think of lost time only provokes infirmity. It is going into the interspace that rouses image to walk, picture to course, and current to run.