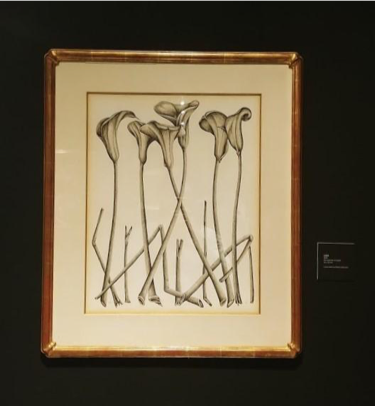

In Lilies, renowned Filipino-American artist Alfonso Ossorio renders flowers, symbols of growth and life, as fragments of bone. They are drawn in pallid ink, exchanging vibrant colors in favor of an emphasis on structure. Their stalks reveal a calcified texture as their cut ends and bent corners harken to worn joints. The flowerheads themselves are petrified in silence, robbed of their hues, hardened, and mineralized.

Alfonso Ossorio (1916 – 1990) was born in Manila to an affluent family from Negros Occidental. He spent much of his early years abroad, studying in England as a child and later moving to the United States where he studied fine arts in the Harvard University and the Rhode Island School of Design. He served as a medical illustrator for the American army in World War II and is a significant figure in postwar American art. Alfonso Ossorio: A Survey 1940 – 1989, showing in the Ayala Museum from February 26 to June 17, is his first exhibit in a Philippine museum.

Inspired by his time in the army, Ossorio’s early work is marked by a fascination with the macabre. As with Lilies, the cohabitation of life and death is evident in Illness and Recovery (The Portrait of Robert)where faces of the same subject are presented in multiple perspectives as the embalmed Robert rests on his bed. One is deathly and decaying grey, another wears pale skin and red hair, the latter representative of supernaturality in Western tradition, and one is alive yet wounded, peeking through a window, staring aghast at his embalmed self.

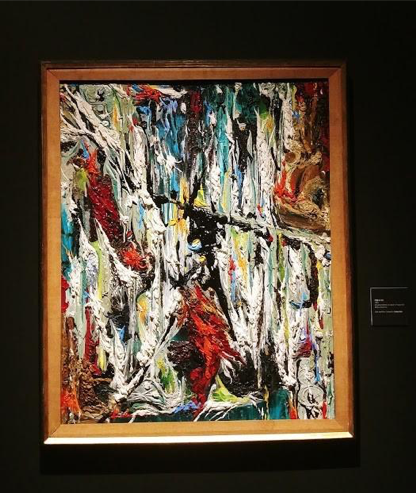

On the other hand, Ossorio’s abstract expressionist paintings take more conceptual forms and makes them fleshy and putrefactive. In an untitled painting from 1958, oil, enamel, and plaster on wooden panel, form a landscape of whites, browns, and blacks. Zooming in, the topography of the artwork is revealed to show rough, scab-like formations and abscess-like drippings. What is inorganic is made alive, albeit rotting.

Similarly, Fire & Ice takes oil and enamel to create a topography of viscous globs and splashes of color on Masonite. The paint ranges from bile greens and clinical blues, to bloody reds and dermal whites, in mounting piles of texture, thereby creating a spectrum of fluids that are organic, bodily, and chaotic.

Ossorio’s project of presenting how the abstract can take a life of its own can most clearly be seen in his assemblages which he calls “congregations,” imparting them with an ecclesiastical meaning. He takes profane objects such as bones, nails, gems, ropes, and other miscellaneous objects and transcends them to art. Ossorio remarks that “even a little piece of plastic or bone is just as alive as the abstract concept of God, which is meaningless unless it is incarcerated.” The profane is the foundation of the sacred. And yet the results of such congregations are often abominable and threatening, imbued with the same air of body horror and death characteristic of Ossorio’s other works.

His quintessential congregation would be Feast and Famine IIwhere bones, spikes, buttons, rhinestones and more compose a hellish monstrosity. Piercing eyes are set on a clown head, adorned with rusted nails, bony horns, and a gaping mouth. The head sits atop a moose’s skull donning eyes that stare into the abyss and ornaments from a confused variety of knickknacks. A bulbous spiked object protrudes from the clown’s crotch, a phallic show of destructive power. True to its title, the congregation takes the remnants of a strange feast to create a figure that evokes a monstrous sort of hunger.

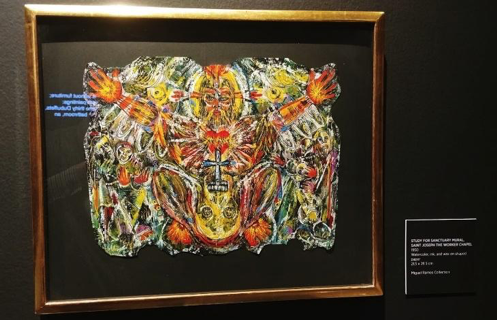

His wax-resist paintings likewise have sacred connotations. Using the element of candles, an important object in venerating the sacred, Ossorio draws figures to later be revealed by a coat of watercolor, as if the result of worship can only wholly be seen in a grander context. The figures drawn range in subject but often depict motifs of religion and suffering.

One of Ossorio’s most famous works is his sanctuary mural, commonly known as Angry Christfor the Saint Joseph the Worker Chapel in Victorias, Negros Occidental. The study for the mural was a wax-resist painting depicting a stern-faced, vindictive Jesus Christ on the top half as and a skull on the other. The painting includes spectral and grotesque imagery in a violent array of reds, pinks, and yellows, contrasting most Christian murals’ celebration of life.

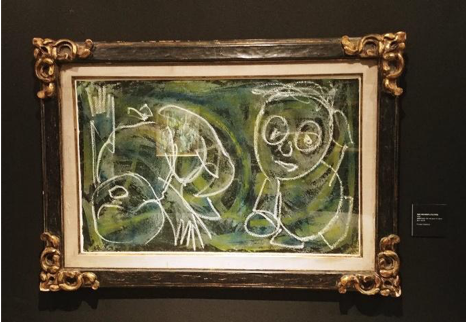

Meanwhile, Two Wounded Children present what the title describes in a disturbingly childlike rendering. Two wax-drawn children are displayed in pain as a sickly green background reveals their haunting shapes. The same tools of the sacred result to the pain of the innocent, shown when the blank spaces of void are filled, when the silence is shattered.

The thread that ties Ossorio’s works together is the assertion of the abstract into the incarnate world, which, his art cautiously warns, can serve as the agent of death in it. Indeed, between the dusk of World War II and the advent of the Cold War, the context of Ossorio’s art is a clash of civilizations, a war between gods. Whose worshipped ideas will prevail? Whose beliefs will be the victor? But, more importantly, in fighting for these beliefs, what monsters and horrors have we produced?